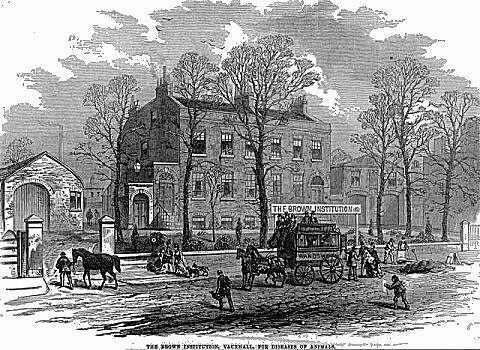

The Brown Institute for Animals

The Brown Institute for Animals in Wandsworth Road was the first animal hospital in the country. In 1855 Thomas Brown M.A., LL.B., who lived in both Dublin and London, left £20,000 to the University of London to found ‘an Animal Sanatory Institution’ which was to be concerned with “investigating, studying, and without charge beyond immediate expenses, endeavouring to cure maladies, distempers and injuries, any Quadripeds or Birds useful to man may be found subject to.” There were many complex conditions to the legacy, with a 19-year time limit in which to set up the institute which had to be located within a one-mile radius of Westminster, Southwark or Dublin. If the time limit was breached, the money was to go to Trinity University in Dublin to set up language professorships. After many legal trials and tribulations, the Brown Institute was set up in Wandsworth Road in July 1871.

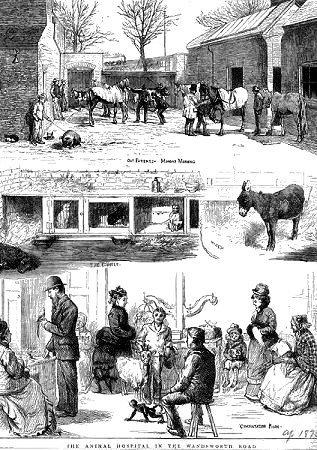

The Institute was made up of two departments – the laboratory and the hospital. In overall charge was a Professor-Superintendent, with help from a ‘veterinary assistant’ (a qualified veterinary surgeon). The first Professor-Superintendent was Dr J. Burdon-Sanderson, who under the terms of Brown’s will had to give at least five free public lectures each year, and the first veterinary assistant was William Duguid MRCVS.

The laboratory, which carried out scientific research on animal diseases, animal physiology, surgical procedures and animal nutrition, was the first pathology lab in the country. Apart from its own research work, it carried out investigations for the likes of the Royal Society and the Army. The other department was for the treatment of sick or injured animals.

One of the diseases that the Institute worked on was rinderpest, or ‘cattle plague’, that had devastated dairy farming in 1865 when 50,000 head of cattle had to be slaughtered. The disease affects mainly cattle but also sheep and goats, and occurs chiefly in central Africa and Asia. The 1865 UK outbreak is thought to have been caused by cattle imported from Revel (Estonia) and sold in the London cattle market which ended up in dairies in Lambeth and Islington. The disease’s symptoms include fever, haemorrhages and diarrhoea. The slaughter and movement of animals had to be strictly controlled to contain the outbreak. The measures taken in 1865 were the forerunner of those used 135 years later for outbreaks of Foot and Mouth. Today animals can be vaccinated against rinderpest.

The Institute was badly underfunded and rather neglected by the veterinary profession but the labs were used by a number of researchers and did make a contribution to medical knowledge, the most notable researchers being Fredrick Twort, Victor Horsley and Charles Sherrington. However, most superintendents concentrated on treating animals and by 1891 nearly 50,000 animals, mainly dogs and horses, had been treated. The busy out-patients section was supplemented by an in-patients section.

The Institute was badly underfunded and rather neglected by the veterinary profession but the labs were used by a number of researchers and did make a contribution to medical knowledge, the most notable researchers being Fredrick Twort, Victor Horsley and Charles Sherrington. However, most superintendents concentrated on treating animals and by 1891 nearly 50,000 animals, mainly dogs and horses, had been treated. The busy out-patients section was supplemented by an in-patients section.

The Institute closed at the start of the war as the Veterinary Assistant left to join the army. The building was hit by German bombs in 1940 and 1943. But the real end came in July 1944 when it was struck by flying bombs causing major damage and never reopened. The LCC compulsory purchased the site in 1953 for £4,700. Following 25 years of legal wrangling the assets were eventually divided between the universities of London and Dublin. The London share was used to endow the Thomas Brown research fellowship in veterinary pathology at the Royal Veterinary College.

This article was researched by Arthur Campbell Water and is based on “The Royal Veterinary College: A Bicentennial History” by Ernest Cotchin published by Barracuda Books 1990 and “The British Veterinary Profession 1791-1948” by Iain Pattison published by J A Allen & Co Ltd 1984.