The Vauxhall district and particularly the Vauxhall Gardens open-air resort was an early hotspot for the ballooning craze that achieved lift-off in the 1780s. As David Coke wrote in an article for Vauxhall History, ‘The Vauxhall Balloon’ set a world record that lasted for three-quarters of a century when it took off from the Gardens in 1836, landing about 500 miles away near Weilburg in Germany.

After the first (hydrogen-powered) Dover-Calais balloon flight in 1785, one of the pilots, a Frenchman, Jean-Pierre Blanchard, set up a ‘Grand Aerostatic Academy’ not far from Vauxhall Gardens in Stockwell Road. (‘Aerostats’ are aircraft such as a balloon or dirigible that derive lift from the buoyancy of surrounding air rather than from aerodynamic motion.)

The first ‘aerial voyage’ in Britain took off in 1784 when Vincent Lunardi ballooned it from Moorfields, London, to Ware, Hertfordshire. His passengers were a cat, a pigeon (caged) and a dog. Letitia Sage was a much weightier proposition, as Sharon Wright tells it in her book Balloonomania Belles: Daredevil Divas Who First Took to the Sky (Pen & Sword). Letitia was an actress who, Sharon writes, became the first Englishwoman to fly. About 100,000 people turned out to see Letitia take to the air on 29 June 1785 in a balloon that was to have been piloted by Vincent Lunardi. Lift-off, when finally achieved, was from Southwark in the grounds of the Rotunda, a hall at the Surrey foot of Blackfriars Bridge.

Ross Davies

The first successful manned balloon flights were in 1783 France, and ‘balloonomania’ spread like wildfire, quickly hopping the Channel to engulf London. It was all so maddeningly thrilling and fashionable that Georgian society was held in thrall.

Astonishingly, given their second-class status, women were in on the act from the start. The ‘lady aeronauts’ were fabulous, flamboyant or just plain fearless as they embraced the sky and all the freedom it promised. And no one was more fabulous that Letitia Sage, who became the first Englishwoman to fly when she ascended in a balloon over St George’s Fields more than two centuries ago.

Early ballooning was all about showbiz and Letitia, a West End actress with steely ambition and a plunging neckline, was more than at home in the limelight. The balloon belonged to flamboyant Italian diplomat-turned-balloonomaniac, Vincent Lunardi. He was ‘the daredevil aeronaut’ about town, while actress Letitia was described as ‘an incomparable beauty’.

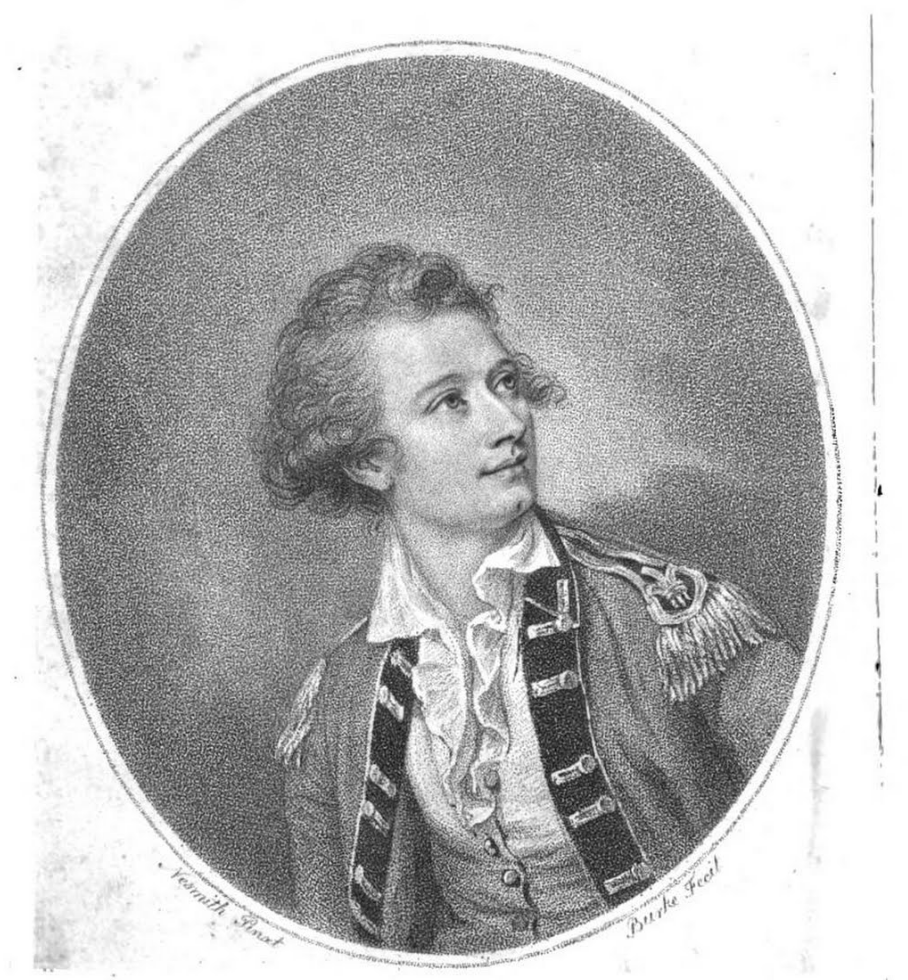

Vincenzo Lunardi, a portrait from ‘An account of five aerial voyages in Scotland’ (1786). London: J. Bell.

Letitia’s moment arrived with Vincent’s invitation to ascend beneath a stylish silk gasbag in front of anyone who was anyone in fashionable London. She would be accompanied by Lunardi and young English gentleman George Biggin and nothing – but nothing – was going to stop Mrs Sage from claiming her place in the history books.

Dressed in a low-cut plum dress with lace cuffs and a large hat adorned with plumes of white feathers, she was ready for her close-up. She stepped out in front of the 100,000-strong Southwark crowd and took her seat beneath the Union Jack balloon beside Lunardi and Biggin.

Then came a nasty surprise. The Italian had invited two more people to join the ascent, including another woman. As far as the actress was concerned, she alone was topping the bill and some flavour of the froideur that descended is suggested by Letitia’s account, which leaves her rival nameless.

The Balloon being as much inflated as was thought necessary to carry up three, if not four persons, at ten minutes after one o’clock (the time specified by Mr. Lunardi for his ascension) I was conducted into the Rotunda, and placed myself in the gallery, in which were Mr. Lunardi, Mr. Biggin, Colonel Hastings (a gentleman to whom Mr. Lunardi had given a promise, that should the Balloon be capable of carrying up more than the intended three, he should have a place in it) and another lady whose name I do not know.

It is here we need to know that Letitia was no lightweight. She had a voluptuous figure and weighed, by her own account, 200lbs. The balloon would not lift but the heaviest person there showed no sign of moving. The lady whose name she did not know proved no match for Letitia and it was game over for the luckless rival.

‘The other Lady was the first to quit the gallery,’ reports the diva, ‘which was merely an act of justice, yielding to my prior claim.’

And then there were four. Letitia was not blind to her ample figure’s effect on grounding the balloon. She still was not getting out, though. A desperate Lunardi stepped down from the basket.

Then there were three. Now the Colonel gave up as well. So then there were two. Two who had never flown in a balloon before. However, Biggin had studied aerostation and Letitia worked in theatre where the show must always go on. With enormous gumption, they took to the air.

The audience went wild and Letitia could enjoy her moment of triumph. She had held her nerve. She had faced down another contender.

She was the first Englishwoman to fly.

John Francis Rigaud, ‘Captain Vincenzo Lunardi with his Assistant George Biggin, and Mrs. Letitia Anne Sage, in a Balloon’ (1785). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Unfortunately, while Letitia contemplated higher things there were those in the crowd with earthier imaginations. When she dipped out of sight an aeronautical legend was born that owed nothing to her version of events.

‘We were crossing the Thames above Westminster Bridge, it was then Mr. Biggin began to lace the aperture of the gallery which served to let us in, and which had been left open by mistake at our ascension. Some other matter at that moment requiring his attention, he desired I would stoop down and finish it; and thinking it better to go upon my knees to do so, gave rise to the report that I had fainted.’

Fainting was the least of the rumours – but that was her story and she was sticking to it. Letitia’s explanation seems reasonable but when Mrs Sage took to her knees while Mr Biggin steadied her by the shoulder, they were forever to be suspected of inventing the Mile High Club.

Double standards meant the gossip could only burnish Biggin’s reputation while blackening Letitia’s and the story has followed her down two centuries of flight history.

If takeoff had been hair-raising, the descent at Harrow promised to be no less dramatic. Biggin crash-landed in a field to be confronted by a furious farmer. Luckily the headmaster and boys of Harrow School appeared over the hill and ran to the rescue, carrying off the two balloonists to an impromptu party.

The next day Letitia wrote: ‘I feel myself more happy, and infinitely better pleased with my excursion than I ever was at any former event of my life.’

Letitia’s coup won her kudos from the New London Magazine: ‘It is perhaps a true observation, that there is no enterprise, however dangerous or difficult it may be, but the female mind can summons courage enough to undertake it. An instance of this we have in Mrs Sage, who unites to the tenderness peculiar to her sex, that manly fortitude that constitutes the heroine.’

This was a counterbalance to the salacious rumours doing the rounds and merciless satirical drawings from James Gillray and George Cruikshank. It’s often assumed that Letitia went to ground because of the curtain controversy but my research reveals the pragmatic star simply carried on with her adventures… but that’s another story.

Sharon Wright is a journalist from Bradford who lives in South West London. She has worked as a writer, editor and columnist for the Guardian, Daily Express, New York Post, Disney, Glamour, Red and Take a Break. She is also the author of critically acclaimed plays performed in Yorkshire and London, including Friller about Edwardian balloonist Lily Cove.

Sharon Wright is a journalist from Bradford who lives in South West London. She has worked as a writer, editor and columnist for the Guardian, Daily Express, New York Post, Disney, Glamour, Red and Take a Break. She is also the author of critically acclaimed plays performed in Yorkshire and London, including Friller about Edwardian balloonist Lily Cove.

‘It was Lily’s story that set me off wondering about the very first women to fly. I came across her story many years ago as a cub reporter, fascinated by her mysterious death near Ponden Hall outside Haworth in 1906. As I unearthed one astonishing story after another I was hooked. From Letitia to poor Lily, I realised the history of the lady aeronauts had never been brought together before. Yet there was the evidence from the original sources of all these truly remarkable women and their incredible adventures. That’s when my skills as a journalist came in, as I slowly pieced together the whole story. Some of the happiest days were spent poring over original cuttings, texts and accounts, including the early ballooning collections at the National Aerospace Library in Farnborough. I’m quite proud of my detective work on these neglected pioneers, they deserve to be remembered.’