Vauxhall History co-editor Naomi Clifford’s The Murder of Mary Ashford: The Crime That Changed English Legal History (Pen & Sword, 30 May 2018) presents new evidence in a notorious 200-year-old case of rape and murder which changed English legal history, leading to the abolition of ‘trial by battle’ as a means of settling murder cases.

Updated 5 September 2018

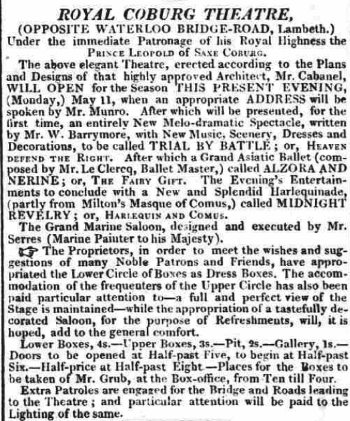

On 11 May 1818, the Morning Advertiser carried an advertisement for that night’s inaugural show of the Royal Coburg Theatre (today’s Old Vic). After a short address by Mr. Munro to mark the opening of the theatre, the main offering was to be the premiere of a new William Barrymore[1]1759–1830. Originally Blewit; an English actor at Drury Lane and the Haymarket; father of the pantomime actor William Barrymore (d. 1845). melodrama, Trial by Battle; or, Heaven Defend the Right, followed by a ‘Grand Asiatic Ballet’ Alzora and Nerine, or The Fairy Gift and closing with a splendid harlequinade Midnight Revelry based on Milton’s Comus.

With Trial by Battle, there was something for everyone, an evening designed to tempt City-dwellers to venture across the new Waterloo Bridge and on to the far-from-respectable Surrey shore. Trial by Battle was nothing if not topical. It must have been in production while the court case that inspired it was still playing out back over the bridge in the Court of King’s Bench at Westminster Hall.

The whole country had been obsessed with the case, which was to decide whether a trial by battle to settle a murder case could be legal. The alleged killer was Abraham Thornton, widely held to have got away with the rape and murder of 20-year-old Mary Ashford. He was being sued by William Ashford, the victim’s brother. Every time Thornton made the journey from King’s Bench Prison at Newington to Westminster Hall, crowds of onlookers jostled to catch sight of him, to hiss or boo him, or better still, to bag a place in court to watch the legal drama unfold.

Thornton was a singular character. Previously acquitted at the Warwick Assizes, he seemed coolly confident that he would win again. Popular opinion, however, seems to have disagreed with the Warwick verdict and held that Justice had not been served. A murderer had gone free and an honest young woman’s death remained unpunished.

Mary Ashford had left a party near Erdington, on the outskirts of Birmingham, late on 26 May 1817 in company with her best friend Hannah Cox, Hannah’s fiancé Benjamin Carter and Thornton. He was a beefy 25-year-old bricklayer from Castle Bromwich who had suddenly latched onto Mary and her friends at the end of the evening. Mary’s bruised and bloody body was found in a stagnant pond early the next morning.

Immediately identified as the prime suspect, Thornton and stood trial for murder at Warwick in August. He admitted to having had sex with Mary but not to murdering her (his solicitor put it about that Mary had killed herself out of a sense of shame). There was general surprise and outrage after his acquittal. Sponsored by the magistrate who had investigated the crime, Mary’s brother William sued Thornton using an ‘Appeal of Murder’, a civil suit of medieval origin designed to give families a means of avenging a death.

The case was heard by four judges at the Court of King’s Bench sitting in Westminster Hall in London and attracted the horrified fascination of people of all ranks of society. Thornton, advised by his smart barristers, countered William Ashford’s suit with his own dramatic challenge. In court, he threw down a white leather gauntlet and declared his right to ‘trial by battel’, that is, hand-to-hand slugging it out in Smithfield with cudgels and shields. Reluctantly, after much deliberation and argument on both sides and many sittings of the court, the four judges were forced to admit that such a process was still legal. The burly bricklayer was free to fight for his life.

The problem for William, Mary’s brother, was that he was a slightly-built lad of 23. Whether or not Thornton murdered Mary, killing William would be no problem. William was forced to withdraw and Thornton won again. Public detestation was so severe, however, that Thornton eventually took himself off to America. Appeal of murder and trial by battle were both expunged from the statute book in 1819.

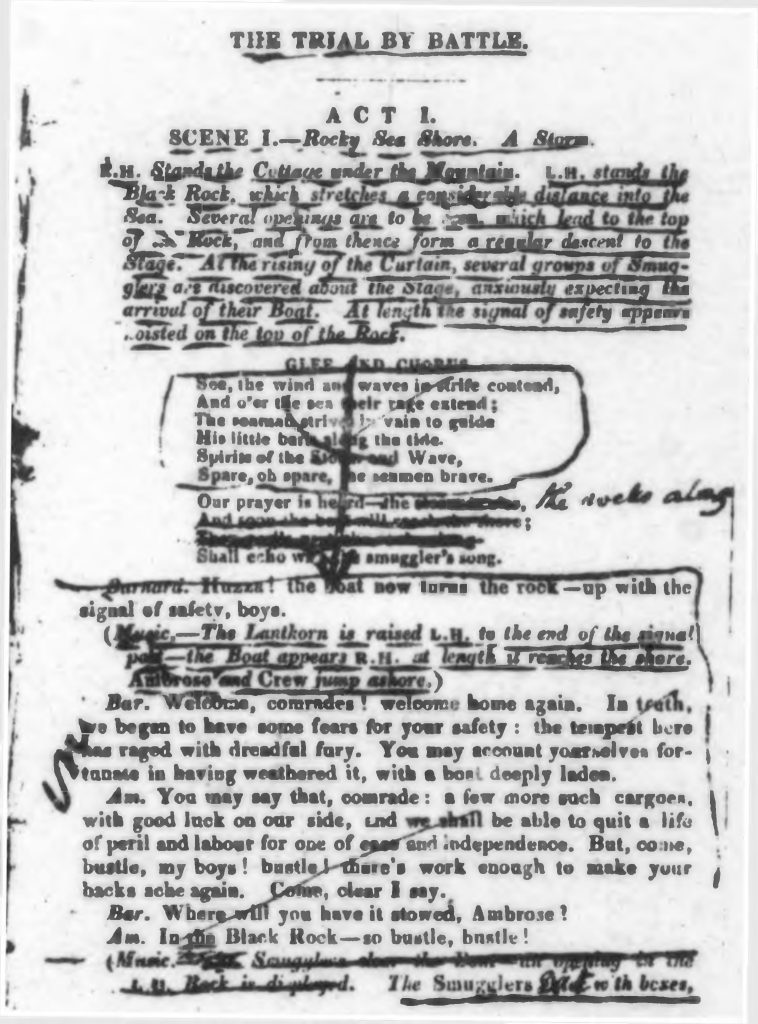

This then was the background to William Barrymore’s melodrama Trial by Battle. As was the convention, the characters were rendered as stereotypes. The action was shifted from England to an unspecified European country and a world of castles and gothic interiors, in an era that was vaguely medieval: Abraham Thornton was now Baron Falconbridge, a ruthless and lustful villain; Mary Ashford, his wronged and virtuous victim, became Geralda, and her brother and champion William was the brave Hubert. But where in real life due process failed to provide the cathartic ending the public craved, justice for Mary and death for Thornton, Barrymore’s Third Act delivered all that supporters of Mary Ashford had wished for.

Barrymore’s play has a band of smugglers, hired by dastardly Baron Falconbridge, abducting Geralda, who has resisted the Baron’s efforts at seduction. Her brother Hubert and father try to protect her, but the Baron kills her father. One of the smugglers, Henrie, who had previously refused to take part in the plot, rescues Geralda while her brother pursues the Baron to his castle. After a trial, the Baron and Hubert agree to combat but it is Henrie, acting as champion for Geralda’s family, who kills the Baron. In the imaginations of the audience if nowhere else, the world was put to rights.

Barrymore, an actor and prolific writer of melodramas, was previously theatre manager at the Royal Surrey and Astley’s Amphitheatre and specialised in spectacular staging. In 1824 he recreated the Battle of Waterloo at Astley’s in a production that included real horses. During this period audiences lapped up entertainment that brought real-life dramatic events to the stage.

On the night of 11 May , however, behind the scenes of the Royal Coburg, things were far from perfect. The doors opened at 5.30 and the performance was due to start at 6.30pm. At that point, the orchestra struck up ‘God Save the King’ and the audience joined in. Mr Munro, a distinguished actor on loan from the Theatre Royal, Edinburgh stepped forward to welcome the audience and give the address. Then, just as the curtain was about to rise on Trial by Battle, Richard Henry Norman, the clown, came on stage. He was very upset and explained to the house that he had been billed to perform in the harlequinade at exactly the same time as he had contracted to appear at Covent Garden. For this reason, he wanted to change the order of the billing and for the harlequinade or pantomime to be performed first. The theatre manager, Mr Glossop, had refused and Norman was now claiming that he was preventing him from getting his costume.[2]Norman had handbills printed up, which he handed to audience members when they entered the building, indicating that the dispute had been going on for some hours, if not days.

After a short pause Mr Munro came forward to speak on behalf of Mr Glossop. He was endeavouring but with little prospect of success to make himself heard when Mr Norman again presented himself to state that “his Clown dress was withheld from him by Mr Glossop.” On this news being received, the uproar became greater than ever.

Mr Munro retired: the curtain was drawn up, and an attempt was made to go through the first scene of the Melodrama; but the strong disapprobation expressed caused its Author, Mr W. Barrymore, to advance, in order to make a new appeal for Trial by Battle and Mr Glossop; he was assailed by a shower of orange peel; the small ornamental railing which surmounted the orchestra partition was torn down and thrown on the stage; two of the lamps in front of it were broken, and the most violent tumult convulsed every part of the house. Mr Norman from time to time came forward to announce that Mr Glossop still retained his dress. To this no answer was given; both parties seemed resolved not to yield …

After many unsuccessful attempts to obtain silence, Mr Barrymore accomplished so much of his purpose as to make it understood that the Managers wished to treat the public with all possible respect, but had been of the opinion that to change the order of th epieces would be to commence with impropriety.

Mr Norman now again made his appearance and offered to speak; but as silence could not be instantaneously procured, he conveyed his meaning to the spectators by a few pantomimic flourishes, which intimated that he had been reinstated in his wardrobe and was going to dress for the Pantomime.

The audience were regaled with music and a comic song by Mr Stebbing in the course of the next half hour and at eight o’clock the performance commence. Mr Norman and Mr T. Blanchard were very amusing as the Clown and Pantaloon.

A great variety of good scenery and some pleasant tricks compensated the holiday folks for the disappointment at first experienced and the exertions of the principal performers were requited with liberal applause. —Morning Post, 12 May 1818

Morning Post, 12 May 2018

The harlequinade included ‘new and extensive scenery, machinery mechanical changes, tricks and metamorphoses.’

The ‘Grand Asiatic Ballet’ Alzora and Nerine was probably performed next, by Mr LeClercq and his wife, and featuring his children and pupils, followed by Trial by Battle.

Cast members were

Baron Falconbridge: Mr Munro (Theatre Royal, Edinburgh)

Albert: Mr Davidge (from the Sans Pareil)

Hubert (his son): Mr McCathy (Theatre Royal, Bath)

Ambrose: Mr Stebbing (late of Astley’s Royal Amphitheatre)

Rufus: Mr Bradley (late of the Surrey Theatre)

Gilbert: Mr Bryant (Surrey Theatre)

Little Jem: Miss J Scott (King’s Theatre)

Morrice (a silly peasant): Mr Harwood (Theatre Royal, York)

Geralda: Miss Cooper (From the Worthing Theatre)

Ninette: Miss E. Holland

According to the Huntingdon, Bedford and Peterborough Gazette the ‘scenes were throughout well executed, and the performances are passable. The house was crowded to excess, and the pieces met with a good reception.’ Whatever the play lacked in literary merit was more than compensated for by glamour and spectacle, and by the new music, scenery, dresses and decorations.

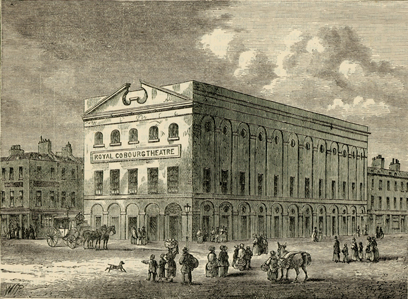

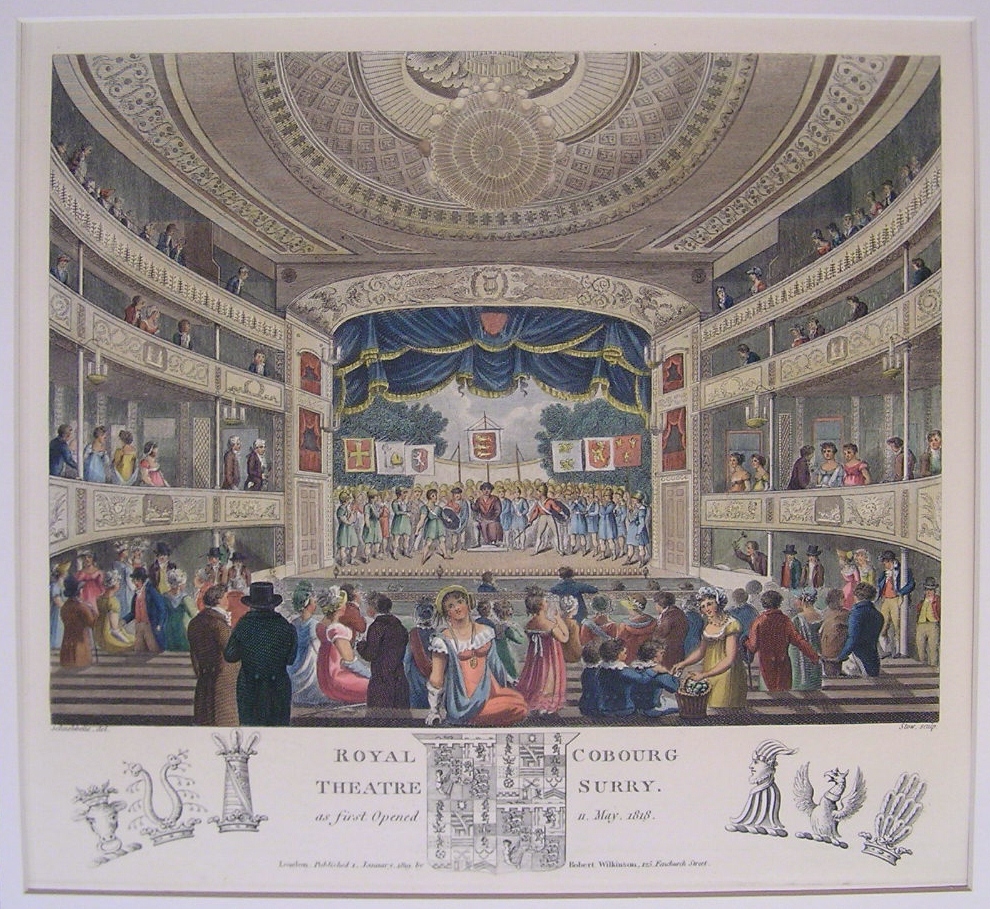

Although the building was plain with a simple classical façade, the design, by Rudoph Cabanel, was ambitious — costs ran to a massive £12,000 — and boasted state-of-the-art scene-painting and property rooms, and an in-house gas-making plant and gasometer. The project itself was the brainchild of Daniel Dunn and James King[3]Dunn and King later dropped out of the project., the lessees of the Royal Surrey, who in 1816 had not been able to meet the rent on that site (it had been increased sharply by the owner) and decided instead to build a new theatre and attract investors. These included the Waterloo Bridge Company and John Thomas Serres, once marine painter to George III[4]Serres’ wife became deluded and claimed that she was the illegitimate daughter of the King’s brother the Duke of Cumberland, leading to the loss of his royal patronage – treatment that … Continue reading. Serres supplied paintings for the ornate Grand Marine Saloon, which was approximately in the area now occupied by the foyer (his subjects included Neptune in a Coach drawn by Sea Horses, the Bombardment of Algiers (1816) and portraits of Princess Charlotte and Prince Leopold[5]All these works are now lost.) and he had helpfully used what remained of his influence with the royal family to obtain the patronage of the daughter of the Prince of Wales, Princess Charlotte, and her husband Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg, after whom the theatre was named. Another saloon in the basement was lined with gilt caryatids supporting the roof and casts from the ancient world, and being in the basement lit with gas.

The theatre had been a difficult build from the start. It was not just that the theatre was built on marshland on the south bank of the Thames – the foundations were made from the rubble of the old north bank’s Savoy Palace on the north side, demolished to make way for Waterloo Bridge itself[6]These foundation stones were supplied by the Waterloo Bridge Company, who had invested in the theatre and had an interest in attracting people to use the toll bridge to attend entertainments south of … Continue reading – but inadequate investment was followed by a walk-out in 1817 of construction workers who had not been paid. The project was saved with a large cash injection from Joseph Glossop, the son of a wealthy local tallow chandler, who appointed himself theatre manager.

The Coburg opened on Whit Monday, 11 May 1818, in an ‘unfinished state’.[7]Allen, Thomas (1826). The History and Antiquities of the Parish of Lambeth, and the Archiepiscopal Palace in the County of Surrey. London: J. Nichols. Even so, it must have been a night to remember. The building could accommodate 3,800 and the orchestra pit up to 30 performers. Gas-powered cut-glass lustres shone over and on either side of the stage, while blue and gold boxes and gilt pillars shimmered.

There are two tiers of boxes. These, as well as the whole interior of the theatre, are painted a fawn colour, ornamented with gold wreaths of flowers, and in the centre of each box is an allegorical painting. The pit and gallery are so constructed, that every part of the stage (which is very spacious) may be viewed from them. The drop scene is a view of Claremont. —Gentleman’s Magazine

Gentleman’s Magazine

Tickets started at 1 shilling (gallery), increasing to 2 shillings for the pit (seated with backless benches) and 3 and 4 shillings for the upper and lower boxes. They were reduced to half price at 8pm.

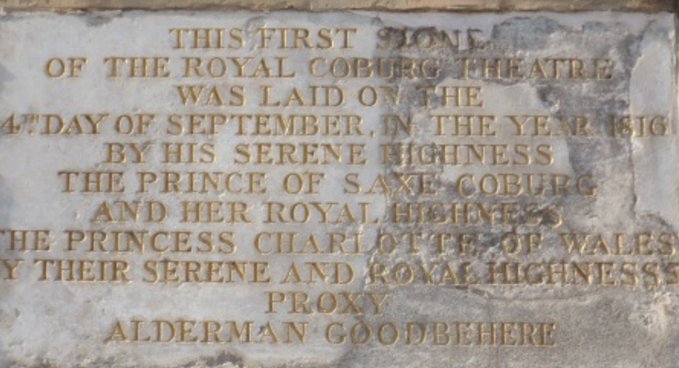

Everyone who attended the opening night of the Coburg would have been aware of the absence of one of its patrons: Princess Charlotte. The 21-year-old heir to the throne was widely admired for her strength of character and for being neither corrupt like her father the Prince Regent nor foolish like her mother Princess Caroline. Charlotte, with her husband Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg, laid a foundation stone at the north-west corner of the Royal Coburg site in September 1816 but had died fourteen months later a few days after delivering a stillborn son. As the theatre audience for Trial by Battle walked through the refreshment room where twin portraits of Leopold and Charlotte hung either side they perhaps reflected for a moment on the fragility of life.

After the performance, the audience exiting the building would have seen that additional lights had been installed in the surrounding roads including the new road to Waterloo Bridge, and the theatre management had also laid on extra patrols to guard against muggers and thieves. Although the Coburg had an advantage over other south London venues, being so close to the new bridge, there was still some reluctance to venture across to the ‘wrong’ side of the Thames.

Barrymore’s Trial by Battle ran initially for 15 nights and was still being sporadically performed in provincial theatres as late as the 1860s. Debate about the guilt or innocence of Abraham Thornton continued for much longer.

Naomi Clifford

The Old Vic will be marking its 200th anniversary with a three-day party comprising a free performance on Friday 11 May, an open house and street party for families on Saturday 12 May, followed by a one-off celebration in the evening, and a gala on Sunday 13 May.

References

| ↑1 | 1759–1830. Originally Blewit; an English actor at Drury Lane and the Haymarket; father of the pantomime actor William Barrymore (d. 1845). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Norman had handbills printed up, which he handed to audience members when they entered the building, indicating that the dispute had been going on for some hours, if not days. |

| ↑3 | Dunn and King later dropped out of the project. |

| ↑4 | Serres’ wife became deluded and claimed that she was the illegitimate daughter of the King’s brother the Duke of Cumberland, leading to the loss of his royal patronage – treatment that looks somewhat unfair given the King’s own problems with delusion |

| ↑5 | All these works are now lost. |

| ↑6 | These foundation stones were supplied by the Waterloo Bridge Company, who had invested in the theatre and had an interest in attracting people to use the toll bridge to attend entertainments south of the river |

| ↑7 | Allen, Thomas (1826). The History and Antiquities of the Parish of Lambeth, and the Archiepiscopal Palace in the County of Surrey. London: J. Nichols. |