Text taken from the Vauxhall Society’s “A guide to the church of St Mary-at-Lambeth, London” by Francis Terry

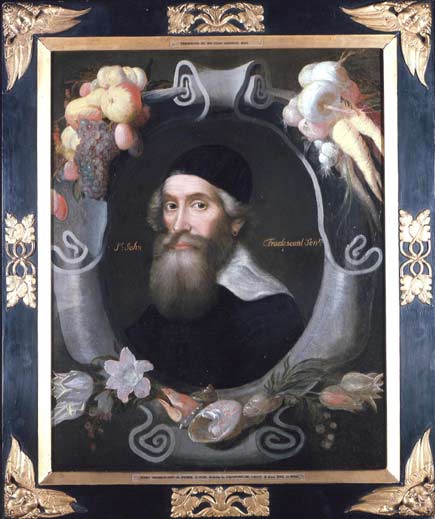

John Tradescant the Elder

John Tradescant the Younger

We are indebted for the material in this section of the Guide to Mea Allan, biographer of the Tradescants. Her book, although out of print, is obtainable from libraries in London and elsewhere. We are also grateful to Paul Pollak of The King’s School, Canterbury, for permission to re-use material by him which first appeared in The Cantaurian for December 1976.

John Tradescant the Elder (c. 1570s–1638)) first settled in Lambeth over 350 years ago. With his son, also named John (right), he was responsible for introducing so many new trees, shrubs, herbaceous and climbing plants into England, that he can truly be said to have founded English gardening as we know it. It is the memory of his life and work which inspires the Trust formed in his name.

Tradescant’s early career was spent as gardener to the Cecil family, for whom he laid out the gardens at Hatfield House in Hertfordshire. Apart from the skill and dedication which he brought to the task, Tradescant also travelled widely in Europe to find new plants with which to stock the

Hatfield garden. In 16 17 he took a £25 share in an expedition to Virginia, from which the plant now known as Tradescantia virginiania (virginiana) remains a minor but lasting memento.

At about this time also, Tradescant was involved with the care and improvement of another garden which had come into the Cecils’ hands at St Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury. After the dissolution of the Abbey in 1538, the buildings were pulled down and the splendid grounds laid out over an area of 16 acres, including what is now Christ Church College, H.M. Prison and the old hospital gardens. While at Canterbury, John Tradescant acted as adviser to Sir Dudley Digges on his new castle at Chilham. With Digges, he went on a ‘Viag of Ambusad’ to Russia in 1618; his account of the journey is now in the Bodleian Library at Oxford. The Russian voyage brought the larch tree to England, as well as a number of lesser plants and some Eskimo artefacts collected in Greenland, as an offshoot of the main expedition. On his return, Tradescant settled in Canterbury with Lord Wootton. His son, John Tradescant enrolled at The King’s School, Canterbury in 1619.

Lord Wootton released his gardener to join another expedition, in 1621, against the Algerian corsairs, who were then harassing British merchantmen in the Mediterranean. Tradescant went as a Gentleman Volunteer, but probably spent more of his time collecting the pirates’ “apricockes”*, their gladioli and the horse chestnut. Perhaps most notable of all, he brought back Syringa persica, the Lilac, as well as further items for his growing collection of ‘rarities”, from Italy, Turkey and the Holy Land.

In 1623, the elder Tradescant entered the service of the Duke of Buckingham, at Newhall, near Chelmsford, where he seems to have acted as a general assistant besides supervising the Newhall gardens. He accompanied Buckingham to Paris two years later where the wedding took place by proxy between Charles I of England and Henrietta Maria. On this occasion he added to his collection ‘little Jeffreyes boots’, which the dwarf Jeffrey wore when he leapt out of an enormous celebratory pie; he also renewed an acquaintance with the French royal gardener, Robin. The false acacia, the robinia, probably grew from a Tradescant seed.

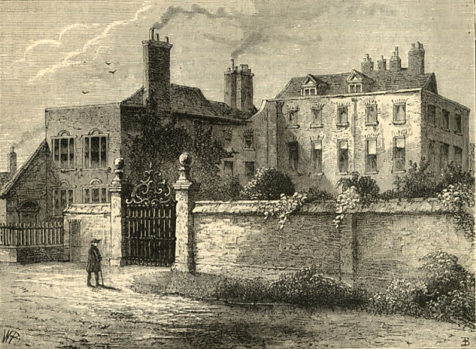

In 1625 or 1626, Tradescant leased an estate in Lambeth from the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury. It was here that his collection, greatly augmented by his son, became not only the most extensive in Europe, but more important, the first accessible to the general public. ‘Tradescant’s Ark’ was recognised as a unique educational asset of the capital: “of all places in England (it is) best for the improvement of children in their education, because of the variety of objects which daily present themselves to them, or may easily be seen (at) Mr John Tradescant’s”, wrote a contemporary schoolmaster. The Ark was a popular attraction for London Society, which came in a steady stream to marvel at the exhibits and the beautiful gardens. The diarist John Evelyn for example records a visit there in 1657. The site of the Tradescant estate is now unrecognisable. The main residence, at Turret House, was demolished in 1881: it stood on the site of the present Tradescant Road and Walberswick Street in Vauxhall, London. Walberswick Street takes its name from the Suffolk village where the Tradescant kinsmen, Robert and Thomas lived.

Tradescant joined another expedition to France with Buckingham in 1627. The voyage was notable for its privations, but it produced once again a contribution to English plant life – the poppy, and the scented stock. After Buckingham’s assassination at Portsmouth in 1628, Tradescant probably remained at his Lambeth property, the gardens of which were fast becoming the premier horticultural nursery in the country. His career reached its peak with his appointment in 1630 as Keeper of His Majesty’s Garden, a post which chiefly involved managing the Queen’s palace grounds at Oatlands, near Weybridge in Surrey.

The younger John (1608–1662) ably assisted his father at Oatlands, becoming a freeman of the Worshipful Company of Gardeners at the age of 26, in 1634 and on his father’s death in 1638, succeeding him as Keeper. He was by this time married to Jane Hurte and had two children, Frances and another John, who died in 1652, ten years before his father. During the period of the Civil War and the Commonwealth (1642-59) it is difficult to know how much time the younger John spent at Oatlands; but some maintenance went on, as is evidenced by the payment of £20 to him by Parliamentary Order (he had asked for £40). He also carried on the Tradescant tradition, in three voyages to Virginia between 1637 and 1654. Although he acquired rights to 100 acres of land there, the real purpose of the expeditions was to gather new plants and exotica.

Tradescantia

The early 1650s were also spent in making a comprehensive catalogue of the contents of the Lambeth Ark. The rust catalogue of the first public museum in this country was published in 1657: Musaeum Tradescantianum, or a Collection of Rarities preserved at South Lambeth near London by John Tradescant. The work is dedicated to the President and Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians, an indication that Tradescant thought of his collection as a contribution to serious knowledge and not a mere rag-bag of novelties. The catalogue has engravings by Wenceslaus Hollar, a friend of the Tradescants.

Tradescants’ House, South Lambeth

In his declining years, John Tradescant the younger decided to present his collection to the University of Oxford; but he wanted his second wife, Hester Pooks to enjoy its possession and the income from it during the remainder of her lifetime. He had become friendly with Elias Ashmole, himself a great collector of curiosities, who put himself in John’s favour by supervising the cataloguing of the Museum Tradescantianum and taking an apparently beneficent interest in its future. He drew up a Deed of Gift awarding the Closet of Rarities to himself, tricking John and his wife into signing it on the pretence that the Museum would, on John’s death, be owned jointly by Hester and himself. Not long after John’s death in 1662, he took Hester to court, gained control of the collection and presented it to Oxford in his own name. The Ashmolean Museum there houses the remains of the collection. Rester Tradescant was, as Ashmole records in his diary, found drowned in her pond in April 1678. She was buried in St Mary’s churchyard along with the three generations of Tradescants.

It is impossible in the space of this short Guide to do justice to the extraordinary range and diversity of the species which the Tradescants collected. In their estate at Lambeth, the family cultivated the first phlox in Britain and the first michaelmas daisies; at Oatlands, the younger John is thought to have first cultivated the pineapple. From the Mediterranean trip of 1621, came a collection of Cistus – amazing shrubs that every day shed their papery petals and next day renew them. From Catalonia came the white jasmine, from Crete, the white lupin; daffodils from Mount Carrnel and Gladiolus byzantinus from Asia minor. There were new vegetables (the Cos lettuce and the scarlet runner bean) and new fruits – the Plantarum in Rorto Iohannis Tradescanti mascentium Catalogus of 1634 lists 55 different varieties of plum.

From North America came most of the spectacular acquisitions of John Tradescant the younger. A beautiful new climbing plant which in autumn turns its leaves to ‘flaming reds and crimsons’ – the Virginia creeper; the tulip tree (Liriodendron tulipifera) and the mimic passion flower. A framed timber walk at the Lambeth estate was covered with excellent vines including two from Virginia, Vitis labrusa and Vitis vulpina.

External links

Museum of Garden History

Tradescant Collection at the Ashmolean Library in Oxford

Tradescantia on the US Department of Agriculture Plants database