During research for the 2023/4 exhibition Georgian Illuminations at London’s Sir John Soane Museum in Lincoln’s Inn Fields (4 October 2023 to 7 January 2024), the museum’s archivist Susan Palmer FSA discovered entries relating to Vauxhall Gardens in the diaries of Sir John Soane and his wife Eliza. Although well known today for his designs for the Dulwich picture gallery and the Bank of England, the personal life of the distinguished architect Sir John Soane is less well known, and his sporadic references to Vauxhall over four decades reveal more than just the odd visit.

By David Coke and Susan Palmer

The son of a bricklayer from Goring-on-Thames, John Soane (1753–1837) was to become one of the outstanding British architects of his time; he was knighted for his work in 1831 and he gave his home in Lincoln’s Inn Fields to the nation as a museum both for his own extraordinary collection of architectural and other antiquities, and for his life’s work. Among the papers he left in his home are his own diaries and those of his wife Eliza, whom he married in August 1784.

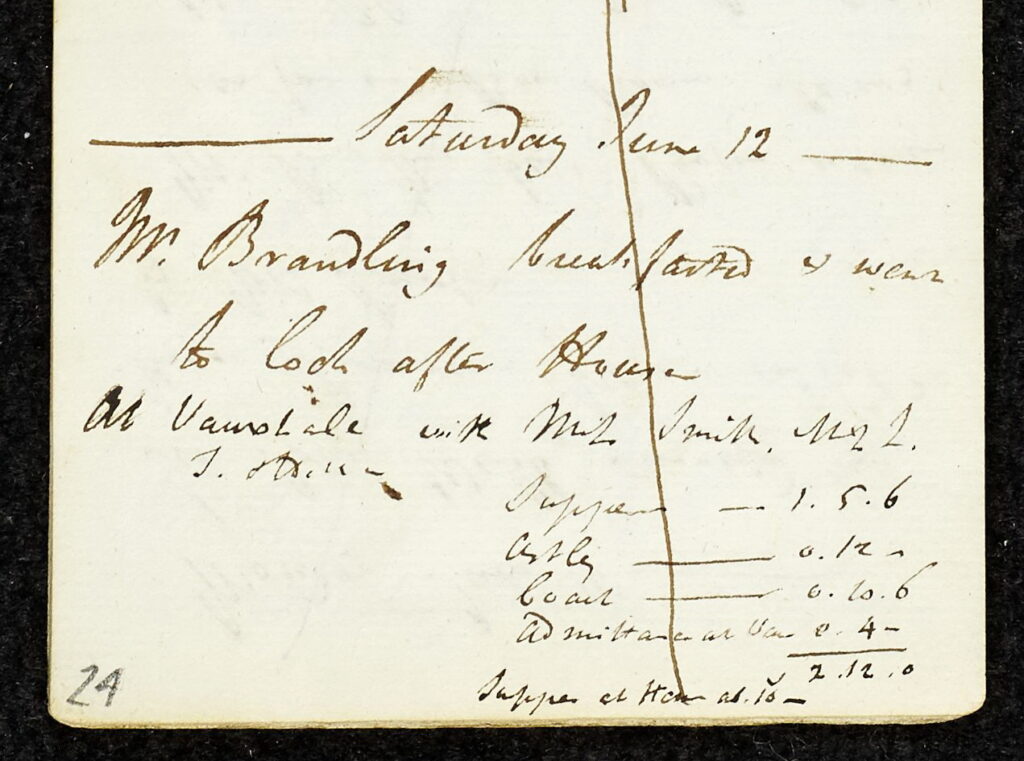

Two months before their wedding, John Soane’s diary for Saturday 12 June 1784 records that he had been ‘At Vauxhall with Miss Smith, Miss L. / T. Oldell’.[1]SNB 11. The ‘Miss Smith’ who accompanied Soane to Vauxhall on that June evening of 1784 was Eliza, soon to become his wife. The two had met the previous year through Eliza’s uncle and guardian, the wealthy London builder George Wyatt. Eliza was just 22 at the time of their Vauxhall visit, and John was eight years older. During 1784 the couple visited the theatre and concert halls on several occasions. The 1784 entry for the visit to Vauxhall is a rare and valuable instance of the kind of courting that is well-known to have occurred at Vauxhall throughout its existence, but of which it is remarkably difficult to find written records. ‘Miss L.’ is probably Eliza’s friend and relative Miss Levick, probably acting as chaperone for the occasion. Making up the party of four, ‘T Oldell’ (if that is indeed the name written – it is not clear, see Fig. 2) is as yet unidentified. At this time, Soane himself was no more than a promising young architect, who had published a book and won several awards at the Royal Academy. Following his Grand Tour to Italy in the 1770s, he had struggled to find significant commissions, but by 1783, this situation was beginning to change; domestic commissions were starting to appear, and he could at last say that he was now a practising and experienced architect with reasonable career prospects. It was only later that his important public commissions, like the Bank of England (1788f) and the Dulwich Picture Gallery (1811–14) would come his way, and make his name nationally.

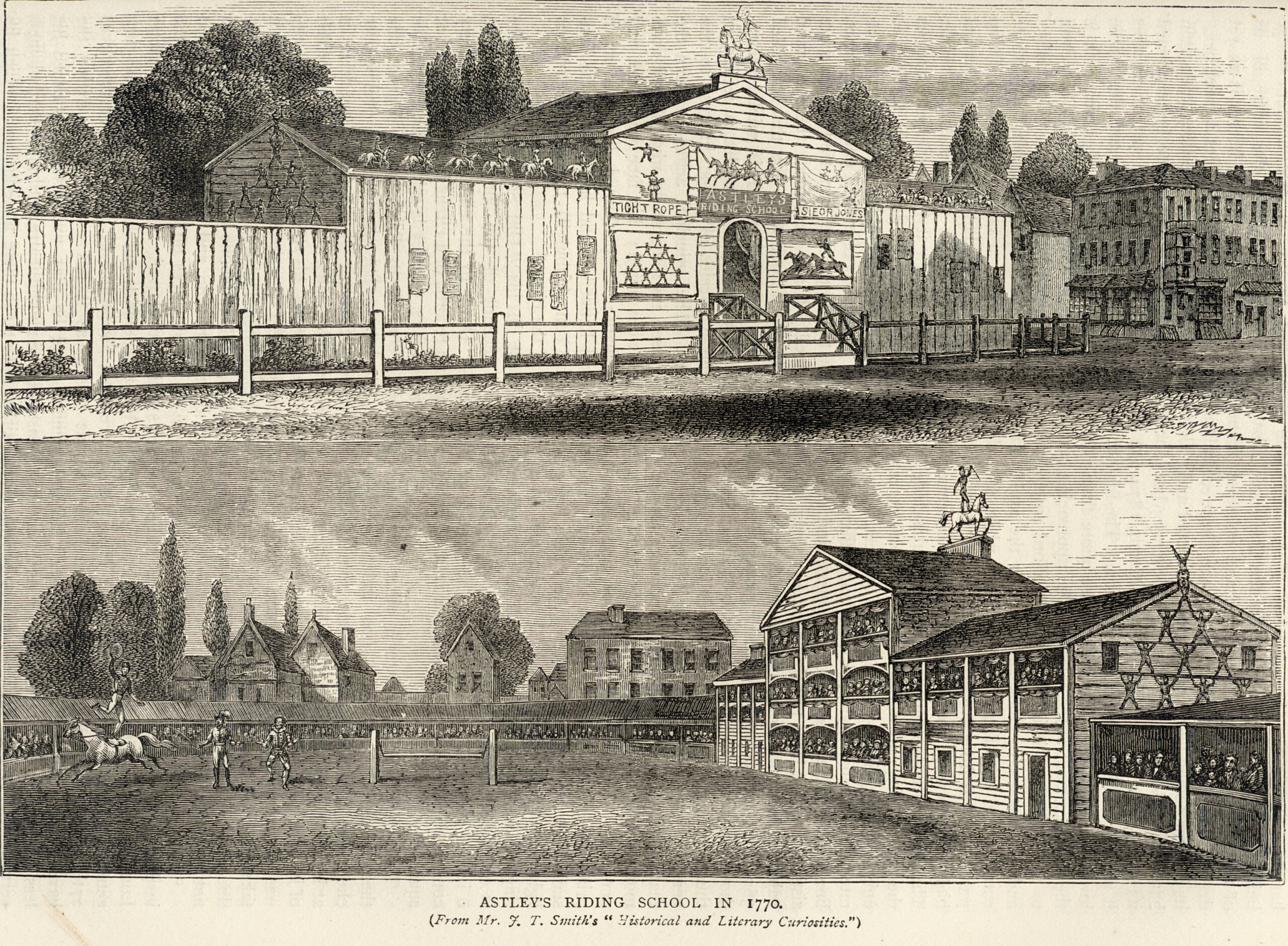

On that June evening in 1784, Soane was careful to keep a record of his expenditure; the admission to the Gardens cost him four shillings (one shilling each), the supper was £1 5s. and 6d. (one pound five shillings and sixpence), and the coach to get everybody to the Gardens from Soane’s house in Margaret Street (between Wigmore Street and Oxford Street), was ten shillings and sixpence. This was an expensive outing by any standard, especially the extravagant supper, but this expense was further increased by an initial visit on the same evening to the circus at Astley’s Amphitheatre, not far from Vauxhall, on the Westminster Bridge Road in Lambeth. Astley’s at the time was an out-door entertainment, so had to be visited during daylight hours, whereas Vauxhall was always well lit and intended to be seen after dark; the visit added 12 shillings to Soane’s overall bill for the evening, which amounted to £2 and 12 shillings. (approaching £250 in 2023). Soane noted that, after Vauxhall, the party returned home for supper at about 10pm, so the notoriously scanty and pricey food on offer at Vauxhall, despite the fact that it must have been a proper meal, with cold meats (ham, beef and chicken), salads, pies, pastries, and wine, had clearly done little to assuage the party’s hunger.

At Astley’s the party would have seen the brilliant equestrianism and acrobatics of Philip Astley and his team, probably with re-enactments of military engagements and of famous feats of horsemanship. This was a very new sort of entertainment for London, but Vauxhall at this time had changed little from its heyday in the 1750s; its main entertainments were still the music and song performed in the outdoor Orchestra. In 1784, the celebrity singer was Frederika Weichsel:

Sweet Weichsel who warbles her wood-notes so wild,

That the birds are all hush’d as they sit on each spray

And the trees nod applause as she chaunts the sweet lay. (1775 song)

Frederika (née Wierman) who had sung at Vauxhall since 1765, married the Vauxhall oboist Carl Weichsel; their daughter Elizabeth grew up to become even more famous than her mother as the great soprano Mrs Billington. Frederika Weichsel can be seen singing in the well-known print called ‘Vaux-Hall’ by Thomas Rowlandson [Fig. 4], in which most of the foreground characters are identifiable. In fact it is likely that Rowlandson’s original watercolour[2]VAM P.13-1967. was made as a leaving gift for Mrs Weichsel, who is the focus of the composition. Immediately behind Frederika lurks the violinist F.H. Barthelemon, who had just retired as leader of the band, and James Hook, the prolific song-smith of the pleasure gardens, whilst the oboist on the left is J.C. Fischer, the son-in-law of Thomas Gainsborough. Behind him, the elderly kettle-drummer on the far left is Jacob Nelson, who dropped dead during a performance there the following year, fifty years after he had joined the Vauxhall band. This composition included several people (like Oliver Goldsmith) who had died before 1784, and the affair between the Prince of Wales and ‘Perdita’ Robinson, alluded to in the picture [Fig.5, detail of Rowlandson], was long over, so the painting represents not a typical evening so much as a fictional grouping of all those characters and celebrities who would have been seen regularly at Vauxhall over the two decades of Frederika’s performances there. It is not difficult to imagine Soane and Eliza among the figures in the background.

By the time of the next diary entry, Soane would already have become a known name around London society; on Tuesday 4 June 1793, just a year after he had acquired no.12 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, where he would eventually move his family and office, he records that he spent the evening at Vauxhall with ‘Mr Collyer &c.’, spending nine shillings[3]SNB 23.. ‘Mr Collyer’ is likely to have been Revd. Charles Collyer, a slightly younger contemporary who Soane had met in Italy, and for whom he had remodelled Gunthorpe Hall in Norfolk, in 1789; Collyer had only recently been widowed, so this trip may have been organised by Soane to help his friend back into society and to recover from his loss. By 1793 the admission fee to the Gardens had doubled, from a shilling to two shillings, so Soane’s nine shillings would not have gone very far if he was paying for a party of three or four people. There is no record of any transport costs, so they may have walked to Vauxhall, as many did, but there was still a river-crossing to pay for, and refreshments to be taken during the visit.

At this period, Vauxhall’s illuminations had become a hugely important feature of the place. The ‘Covered Walks’ next to the supper-boxes were the ideal vehicle for splendid displays of thousands of coloured lamps hung in swags of greenery between the columns [Fig. 6]. An advertisement published in the previous year let the public know that ‘The Colonnades will be Illuminated with every brilliancy that Novelty and varied Fancy can devise’.[4]Unidentified news clipping, CVRC 0970. The same advertisement talks of the ‘Superb Decoration of the Rotunda, in form of an Eastern Tent’ as well as the ‘New Cascade’, an illuminated artificial waterfall made from strips of tin on endless belts turned by Vauxhall’s staff for the fifteen minutes of its display. Soane would no doubt have seen all of these features, but his conversation with Mr Collyer and his party would certainly have included concerns about the upheavals across the Channel in France, and the recent declaration of war between Britain and France. This worrying situation was even reflected by Vauxhall’s proprietors, who ran only a shortened season in 1793.

Six years later, while the Directoire in France was staggering to its collapse, Vauxhall appears in Soane’s Journal on 12 August 1799,[5]Journal 4, p.210; the diary for this date is missing. although not in a very favourable light: ‘Mr & Mrs Malton & Macklew dined here & dragged me to Vauxhall. Exp. £0.11s.0d Coach £0.7s.6d’. That he had to be ‘dragged’ to Vauxhall suggests a certain unwillingness, but whether this was through weight of work or mere lack of enthusiasm is not certain. What is clear is that Soane was on his own without his family at this date, because ‘Mrs S & Children left Town for Margate’ on 28 July,[6]Journal 4, p.209. and had not yet returned, so he may have wanted to get on with work uninterrupted while he could. However, the entry records that he did not return home until 2.15 the following morning, so he cannot have been so very unwilling. ‘Mr Malton’ would have been Thomas Malton the Younger (1748–1804), the artist, whose son Charles was later apprenticed to Soane. A few years earlier, Malton had been employed to paint scenery at Vauxhall, so he knew the place very well; and ‘Macklew’ was probably the bookseller and publisher Edward Macklew, whose work would have brought him into contact with Malton.

By the end of the 18th century, besides some spectacular firework displays, Vauxhall’s illuminations included vast outdoor emblematic transparent paintings, lit by oil-lamps from behind, and strategically set at points in the Gardens where they could be viewed from a distance; these ‘transparencies’, painted in coloured varnishes on linen, would be revealed after dark by the lifting of an opaque ‘Day Scene’ to astonish visitors with the glowing painting behind.

Leaving the Gardens at around 2am, Soane and his party would have had plenty of time to view all these novel features. He could also have heard the famous boy treble Master Gray in his first year of public appearance, singing the traditional Scots lament called The Flowers of the Forest. Some of the most popular songs this year were patriotic calls to duty – Mrs Rosemond Mountain’s much repeated song Loves Volunteer calls on the ladies to persuade their men to join the army, and tells the men that they will only deserve the love of a good woman if they do their duty. Soane himself was quarter-master of the Bank of England’s Volunteer Association, so did not shirk his duty, even though he was in his mid-forties and a married man with a young family.

The final Vauxhall visit recorded in John Soane’s papers was on 12 August 1822.[7]SNB 173. Soane’s wife Eliza had died seven years earlier aged only 53, just two years after the couple had moved into 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, but Soane himself lived on into old age, dying in 1837 aged 83. On this last Vauxhall visit, he was accompanied by Mr and Mrs Purney Sillitoe, for whom Soane was designing a new house in Staffordshire; they were accompanied by ‘Miss Davies & Miss Hibblethwaite’. The Sillitoes lived near to Lincoln’s Inn Fields at 25 Bedford Place, Russell Square. Living with them, at least from c.1820, was Miss Frances Davies, Eliza Sillitoe’s younger unmarried sister and Elizabeth Hibblethwaite, an old school friend of Eliza’s, who is recorded in the 1851 census as having been born in the West Indies[8]David Jenkins, The History of Pell Wall – its Estate and its Owners. Unpublished typescript by for the Pell Wall Preservation Trust, deposited in the Soane Museum Research Library. There are frequent diary references in 1822 and subsequent years to the Sillitoes and their two companions socialising with Soane.

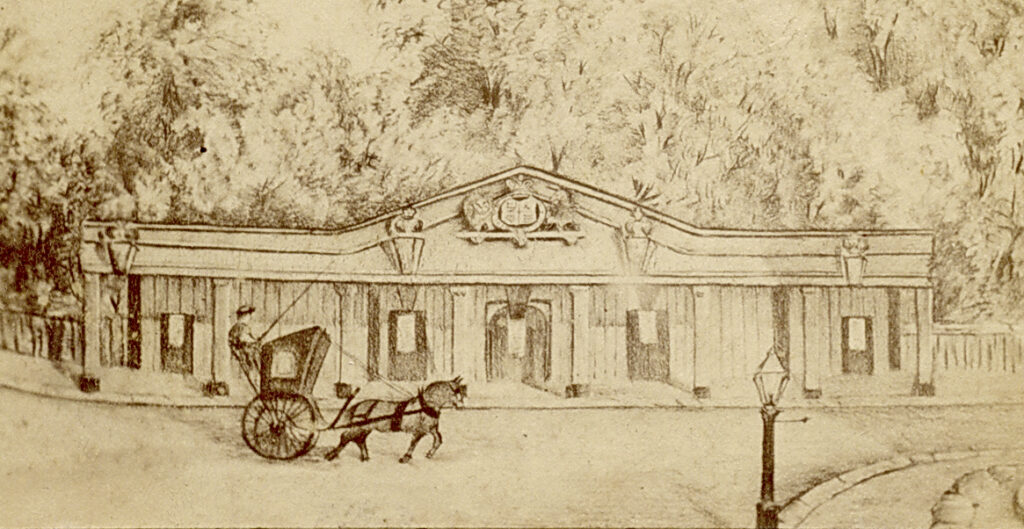

By the 1822 season, Vauxhall Gardens had altered significantly, and if Soane had not visited for over twenty years, he would have noticed huge changes. In the first place, the Gardens had been re-branded, with the permission of the recently-crowned King George IV, as The Royal Gardens, Vauxhall [Fig. 7 shows the coat of arms]. As Prince of Wales, George had been a regular visitor to the Gardens, which, with its Prince’s Pavilion and ubiquitous Prince’s feathers, had become the equivalent of a public Court for successive Princes of Wales. Also, The Royal Gardens, Vauxhall were now under new management; the Tyers family had leased the Gardens to the partnership of the businessman and printer Frederick Gye and the lottery agent Thomas Bish, who were later joined by the theatrical entrepreneur Richard Hughes.

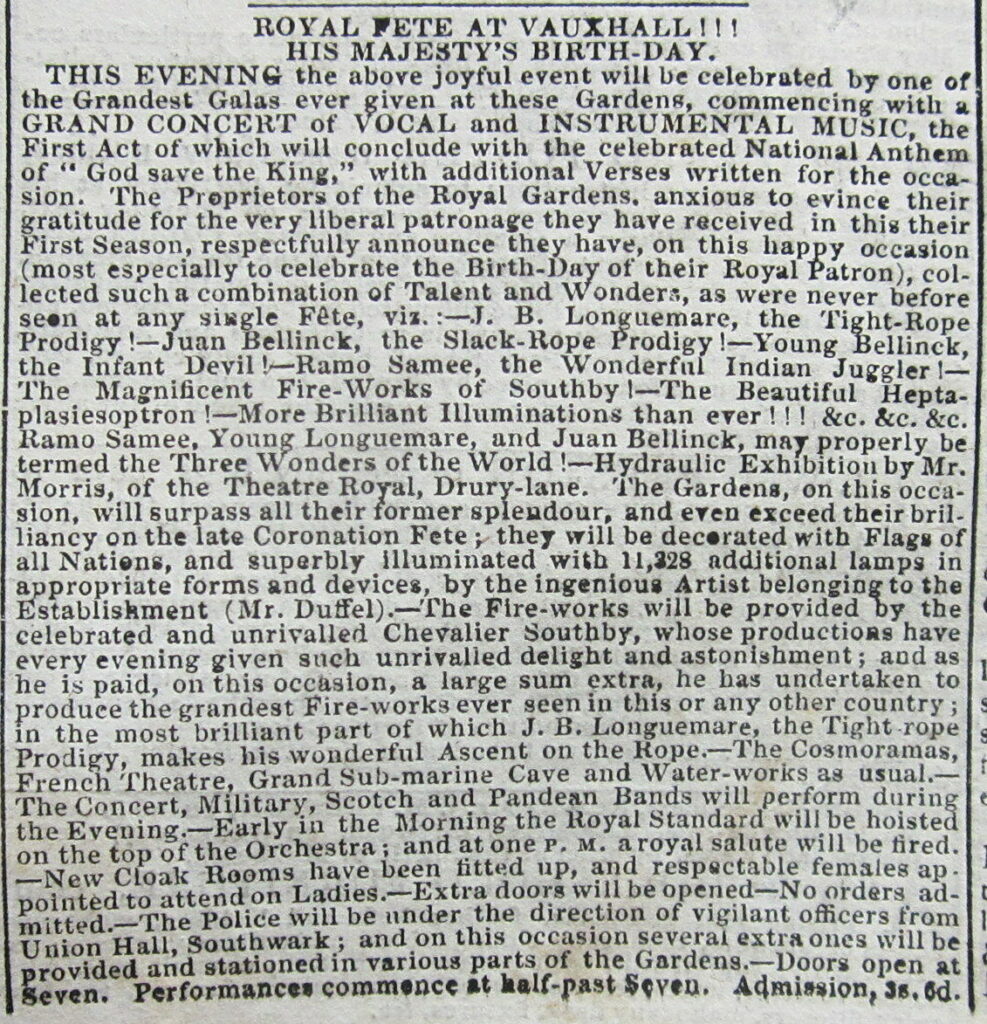

In their first full year as lessees, Gye and Bish turned Vauxhall from a sedate and aristocratic music venue into a more commercial mass entertainment, with new buildings and attractions including the French (or Mechanical) Theatre, and the Submarine Cave with ancillary buildings like new cloakrooms and a new fountain. Popular attractions had been added such as the ‘Wonderful family’ of French tightrope walkers and the ‘Wonderful Indian Juggler’ Ramo Samee, with comic acts like Fred Yates’s ‘Hasty Sketches’ (with comic situations, stock characters, impressions of famous actors and singers). The new proprietors were rewarded that season by the largest ever attendance, averaging almost 3,500 visitors every evening of the season. What Soane may have thought of these acts, or indeed anything he saw at Vauxhall over the years, remains unknown; as ever, though, he kept a careful note of his expenditure, which on this occasion was twelve shillings.

Vauxhall’s proprietors were always keen to mark royal occasions, and royal birthdays gave an annual excuse for added celebrations. 12 August 1822, the date of Soane’s visit, was marked by a ‘Royal Fete’, ‘one of the Grandest Galas ever given in these Gardens’, to celebrate the birthday of the King George IV. A long advertisement for the occasion appeared in the Morning Chronicle on the same day, much of which was repeated verbatim in a follow-up report the following day.

It is interesting to note in passing that no record has yet been found in the Soanes’ notebooks or diaries of any visits to Vauxhall’s main competitor, Ranelagh Gardens in Chelsea. Ranelagh closed in 1803, but it had been open for all of John Soane’s life before that. Ranelagh’s architecture, with its impressive Rotunda, its fine William and Mary House, its classical mouldings and figures, its arches and grandeur, had a great deal more in common with Soane’s work at the Bank of England than anything he could have seen amongst the frivolity and exoticism of Vauxhall’s buildings. But maybe that is precisely why Soane (and many others) preferred Vauxhall – it represented a complete break from his everyday work and life, where he could just relax, and smile with his friends at the merriment of the crowds of visitors, the popular songs, the architectural sharawaggi, and the foreign entertainments.

Although the 1822 visit was the last recorded by John Soane, there are two additional visits to Vauxhall recorded by his wife Eliza in her own notebooks. These visits, which occur on two adjacent days, 25 and 26 July 1804[9]MrsSNB 2., a Wednesday and Thursday, are in many ways the most interesting relevant entries in the Soanes’ diaries. Eliza records on the Wednesday that her husband had gone away on a trip to Somerset to visit his friend Admiral Hood for whom he was adapting and extending a house called Cricket Lodge. Soane’s absence appears to have sparked in Eliza an urge to entertain her household, and on the Wednesday, she notes that ‘Servants went to Vauxhall’. This is a rare record of what must have been an outing paid for by their employer, which again is something that is known to have happened throughout Vauxhall’s history, but which is not normally recorded so definitively. At this date the Soanes employed five live-in servants – a butler, a footman, two housemaids and a cook. The butler in 1804 was William Nicholls and the footman R. Junells; their first names are not given in the source, which in this instance, is a tax return, but William Nicholls is recorded elsewhere. The two housemaids were Ann Collard and Mary Nicholls. The Soanes always had a female cook, and in the will of Sir John Soane, written in 1833 he leaves his cook, Mary Evans, a generous annuity of £40, whereas some of his other servants at the time received lesser annual sums of between £12 and £20. Ann Collard is also mentioned in Soane’s will, with an annuity of £15. These are generous bequests, especially the £40 a year to Mary Evans, suggesting that she was an old family retainer, and may well have been present for that Vauxhall trip in 1804. It is likely that the Vauxhall party on 25 July 1804 included five people.

The Soanes are known to have treated their servants well and many of them stayed with the family for several years. Indeed Mrs Barbara Hofland, the authoress and friend of the Soanes, writing to her mother immediately after Mrs Soane’s death in November 1815 describes her as ‘the best possible mistress to her servants, who adored her’.[10]Susan Palmer, At Home with the Soanes, in Upstairs Downstairs in 19th Century London. London: Pimpernel Press, 2015. p.17.

The next day, on the Thursday (26 July 1804), Mrs Soane writes in her diary[11]MrsSNB 2, ‘Went to tea at Miss Levick’s to meet Mrs Corny &c. in the Eveng at Vauxhall with boys & Mrs Wheatley, lost the Ticket. ‘Mrs Wheatley’ was Clara, widow of the artist Francis Wheatley (1747–1801), who had been left in rather straitened circumstances by the death of her husband, and was befriended by the Soane family, who often invited her to join them on family outings and holidays. The ‘boys’ were John and Eliza’s two surviving children, John (born in April 1786) and George (born in September 1789) [Fig. 10]. The boys would have been aged 18 and 14 at the time, and this may have been their first visit to the famous Vauxhall Gardens. Vauxhall’s admission price had risen again, to three shillings, so Eliza would have had to pay twelve shillings just to get in, on top of the cost of transport and refreshments, having paid fifteen shillings for the servants’ tickets on the previous day.

What Eliza means by ‘lost the Ticket’ is not clear; it is to be hoped that she did not lose it before arriving, but that she had maybe wanted to keep it as a souvenir and had lost it during the evening. The fact that she had a ticket in the first place may mean that she was given a pass by her husband before he went away, so that she would not have to pay out of her own pocket – tickets were not given out at the entrance for those who paid at the door.

The illuminations at Vauxhall in 1804 would have been even more spectacular than they were in the 1790s, with tens of thousands of multi-coloured lamps on the trees, the arches, the Covered Walks and most of the buildings, especially the central Orchestra; the facade of this building was almost covered with little oil lamps, which, like the other lamps around the gardens, would have been lit all at once by an arrangement of cotton fuses set up during the day [Fig. 11]. Before the days of electric or even gas lighting, this special effect of the Vauxhall lamps was one of its great attractions, and one which visitors came to see from all over the world. By 1804, Vauxhall’s fireworks were directed by ‘the celebrated female artist’ Sarah Hengler,[12]Morning Post, 13 June 1804. whose Vauxhall displays were some of the finest to be seen anywhere.

Whether Vauxhall’s illuminations had any influence on Soane’s ideas about lighting and his own celebratory tableaux of lamps is not known, but the way the Gardens were illuminated must have left an impression on the architect, whether positive or negative; it would have been impossible to visit Vauxhall after dark at any period of its existence without being deeply impressed by its brilliant lighting. Soane’s interest in the illumination of domestic interiors is well known, and his understanding of how light, and even different colours of light, could affect human moods and emotions may in part have had something to do with his early visits to Vauxhall, where the proprietors had an active and positive interest in the moods and emotions of their visitors; it was vital that they felt relaxed and happy as they walked around the gardens, or sat down for supper, and the lighting always played its part in this.

References

| ↑1 | SNB 11. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | VAM P.13-1967. |

| ↑3 | SNB 23. |

| ↑4 | Unidentified news clipping, CVRC 0970. |

| ↑5 | Journal 4, p.210; the diary for this date is missing. |

| ↑6 | Journal 4, p.209. |

| ↑7 | SNB 173. |

| ↑8 | David Jenkins, The History of Pell Wall – its Estate and its Owners. Unpublished typescript by for the Pell Wall Preservation Trust, deposited in the Soane Museum Research Library. |

| ↑9 | MrsSNB 2. |

| ↑10 | Susan Palmer, At Home with the Soanes, in Upstairs Downstairs in 19th Century London. London: Pimpernel Press, 2015. p.17. |

| ↑11 | MrsSNB 2 |

| ↑12 | Morning Post, 13 June 1804. |