By the 1850s, the management of the world-famous Vauxhall Gardens was looking for a big, new attraction, and they did not come larger than the 1851 ‘Picture-Model’ of the Temple of Concord near the Forum in Rome. This was a huge outdoor canvas, roughly as high as five double-decker buses and as long as six. When the time came to make way for another Vauxhall Gardens attention-getter, the wind-battered, rain-soaked ‘Temple of Concord’ was probably cut up into small canvases and sold to artists. If so, how many Victorian paintings are backed by a bit of Vauxhall Gardens history?

by David E. Coke

‘The largest Painting ever undertaken’ was displayed at Vauxhall Gardens at the opening of the 1851 season, during the Gardens’ final decade. The painting’s vital statistics were proudly proclaimed in Vauxhall’s publicity as 250 feet wide and 80 feet high (76 x 25m), on 10,000 square yards (8,400 square metres) of canvas. It would be hard to disagree with the claims of the proprietors, but how and why did Vauxhall’s painted decorations become so massive?

In its final two decades, the 1840s and 1850s, Vauxhall Gardens was beginning to look rather tired and its press coverage was not always as positive as it had been in the early days. The Illustrated London News, founded by Herbert Ingram in 1842, reported that the Gardens had been struggling for several years to attract the required numbers of visitors, but that, in the editor’s opinion, they could succeed once more if only the proprietors would invest significantly and be more creative and innovative. Other rival attractions were succeeding, to Vauxhall’s detriment, so ‘the amusements must be entirely re-organised; something should be shown to the public which, from the very nature of the place, they cannot see anywhere else.'[1]Illustrated London News, 13 June 1846.

One of the greatest threats to Vauxhall came from the new music-halls, and these, of course, were not vulnerable to the unreliable British climate as Vauxhall still was.

Vauxhall’s greatest asset was its huge outdoor space. This had allowed the proprietors to promote balloon ascents, reconstructions of the Battle of Waterloo, and large illuminated panoramas and other scenes. Vauxhall’s visitors could virtually travel the world through vivid representations of many different places, whether the exotic east, India, or the Alps, Mexico, Russia or Venice. Even the Arctic had been shown, complete with icebergs. British landmarks were also popular. But this sort of scene too was beginning to be available indoors in several London venues, urging Vauxhall’s artists to new extremes.

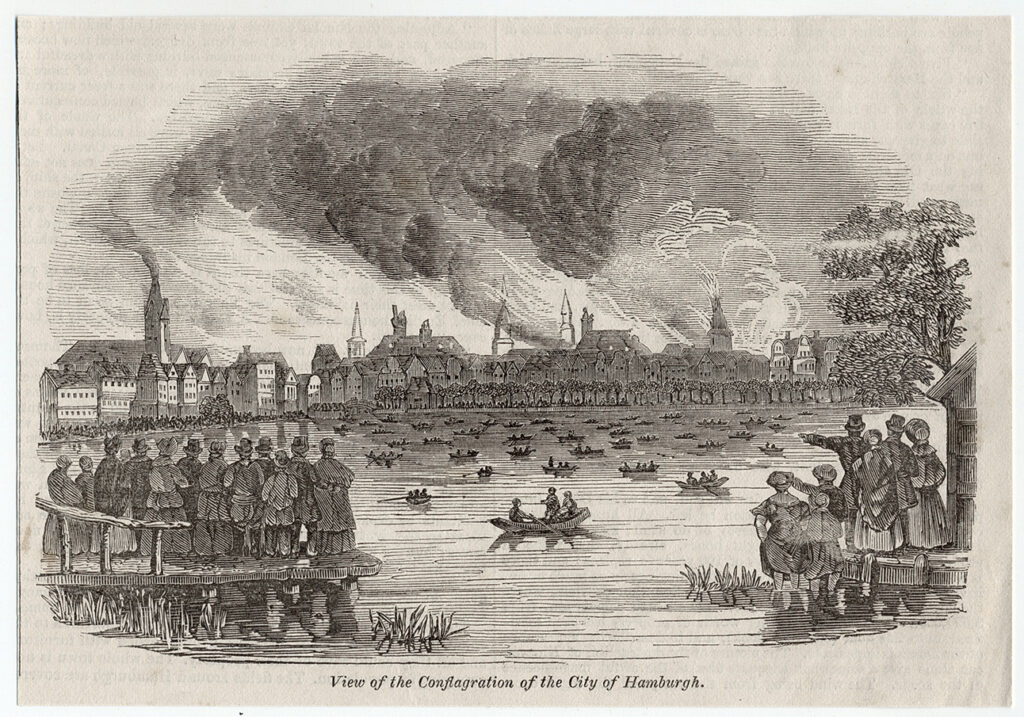

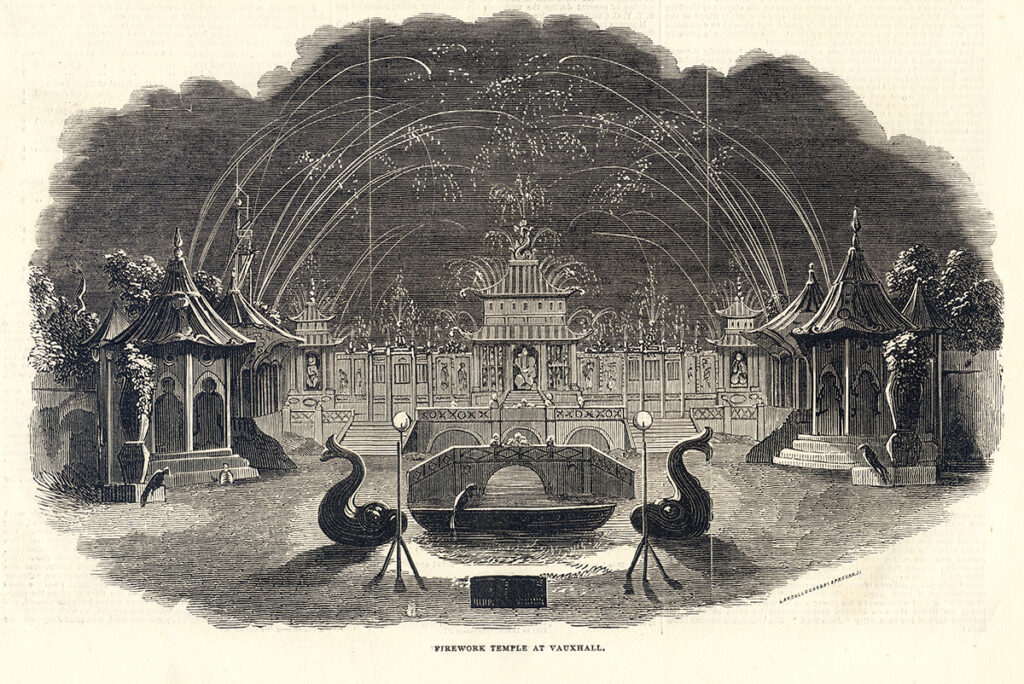

Vauxhall was one of the few sites where fireworks were displayed on a regular basis, and there is no doubt that they continued to be loved by visitors (although not by local residents). One ambitious scenic artist who had seen the fireworks and thought ‘outside the box’ was Charles Marshall (1806–1890), scene painter to the main London theatres; his new idea was to combine Vauxhall’s strengths to construct a new and entirely site-specific attraction which no mere indoor venue could hope to emulate – huge panoramas with spectacular pyrotechnic displays. It was, ironically, the first issue of The Illustrated London News (14 May 1842) that may have provided Marshall with his first inspiration for the kind of subject that would be guaranteed to draw an audience – sensational, dramatic and topical. The image on the front page of the first issue of the magazine showed the great fire of Hamburg [Fig.1], which had raged through the old city only a few days earlier, with devastating results for the populace. A scenic view of a foreign city that was more than just a view – given the right pyrotechnic effects, the audience could marvel at the beauty of the city as dusk fell, then the sudden outbreak of fire in a cigar factory on Deichstrasse, the watchmen’s alarm horns, the fire’s spread through the tinder-dry streets of timber houses, church steeples tumbling, explosions as buildings were blown up to create fire-breaks, and the eventual defeat of the fire by a contrary wind.

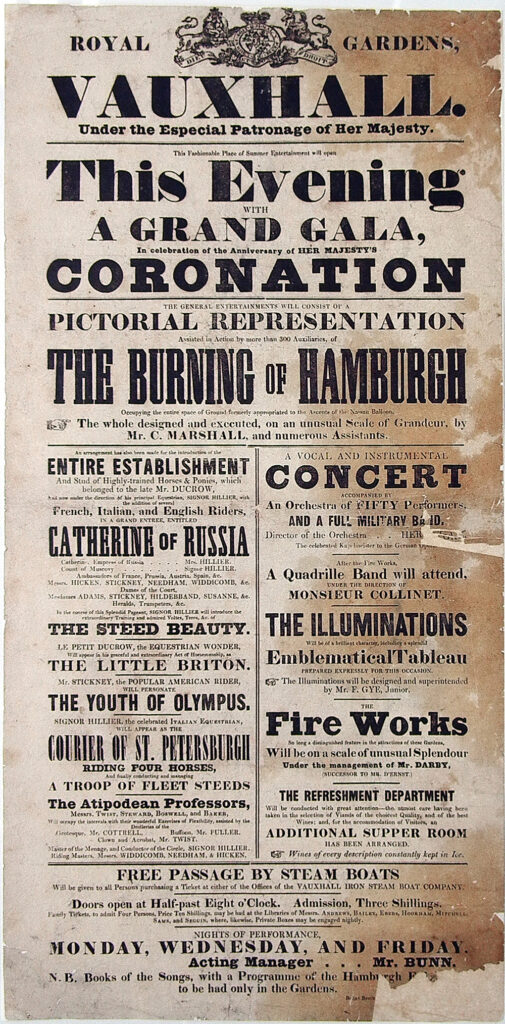

For the full effect of this spectacular display, Marshall needed the cooperation of an expert in fireworks. The lead pyrotechnician at Vauxhall between 1842 and 1851 was Henry Darby, who later referred to himself in his own publicity as ‘Artist to the Nobility and Gentry, Grand Fêtes, Theatres and Public Gardens’, and ‘Sole Artist to the Royal Gardens Vauxhall’. Later in the century he could claim to be ‘Artist in Fire Works to Her Majesty’, so he must have been good at his job. The date chosen for the first display of his Hamburg scene was the fourth anniversary of Queen Victoria’s Coronation – 28 June 1842. Handbills trumpeted the ‘Pictorial Representation, assisted in action by more than 300 Auxiliaries, of The Burning of Hamburgh occupying the entire space of Ground formerly appropriated to the ascents of the Nassau Balloon. The whole designed and executed, on an unusual Scale of Grandeur, by Mr. C. Marshall, and numerous Assistants.’ [Fig.2]

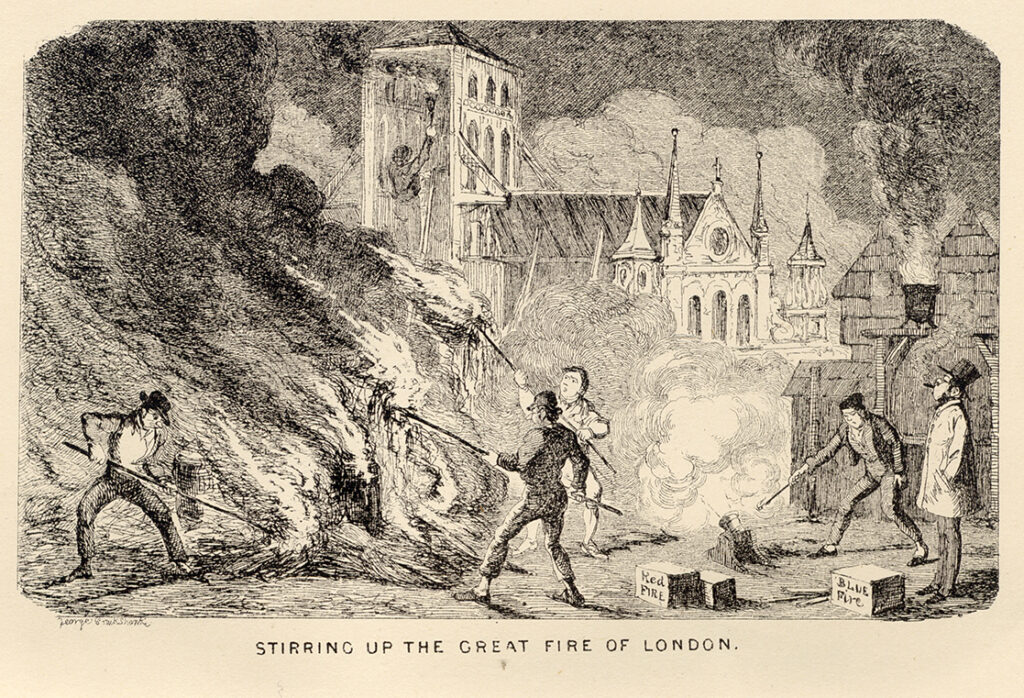

Marshall created the city as a three-dimensional scale-model, made from painted timber and canvas, to a scale large enough to look real from a distance, but small enough to be fitted into the space, with the river in the foreground, to separate it from the audience, and to provide a reflective surface to magnify the effect. The three hundred ‘auxiliaries’ – probably Thames boatmen who doubled up as London firefighters, worked behind the model buildings, creating fires in metal braziers with clouds of smoke, and collapsing many of the structures on strategically-fitted hinges, all to a strict choreography. [Fig.3] The burning of Atlanta, a historic event of 1864, when reconstructed using similar means for David O. Selznik’s classic 1939 film Gone with the Wind, had an equally sensational effect.

As usual at Vauxhall, the Hamburg display was just one of the many irresistible attractions to be seen that evening, but the early 1840s was a low moment in Vauxhall’s entertainments. A press notice of August 1841 sums up the state of the place – writing about a recent masquerade, a journalist writes ‘If there was little to amuse, there was nothing to offend. The affair was stale, flat, and, it may be, unprofitable. There was little dancing, less music and altogether a lack of anything to excite or animate. The whole was stagnant, vapid, and dreary.’[2]The Standard, 28 August 1841. This was not a lone voice at the time.

Despite the success of the Burning of Hamburg in 1842, marred as it was by unfavourable weather, the Gardens did not open at all in 1843, but the following year Robert Wardell was employed as manager, and it was Wardell who offered the Gardens to the troupe of ‘Ioway Indians’ brought over from America by George Catlin. The Ioways needed a spacious but secure place to set up their encampment, for which the Waterloo Ground at Vauxhall was ideal. Wardell created a late season from mid September for a month, allowing the public to come and see the ‘exotic’ foreigners showing off their sports, dances and horsemanship; even though these displays had to be held in daylight, curious visitors arrived in their thousands, and the income gave Wardell a useful capital fund for his proposed improvements.

Before coming to Vauxhall, Robert Wardell had printed and published a newspaper called The Britannia, which probably gave him an appreciation of the efficacy of good marketing; it was during his management of Vauxhall from 1843 to 1856 that the Gardens saw a late revival in its fortunes. As a newspaper man, Wardell clearly saw the potential of Marshall’s ‘Burning of Hamburg’, and his time at Vauxhall was to see the highwater mark of ‘Tableaux Pyrotechniques’ or Picture-Models, an attraction that Vauxhall did bigger and better than anyone else.

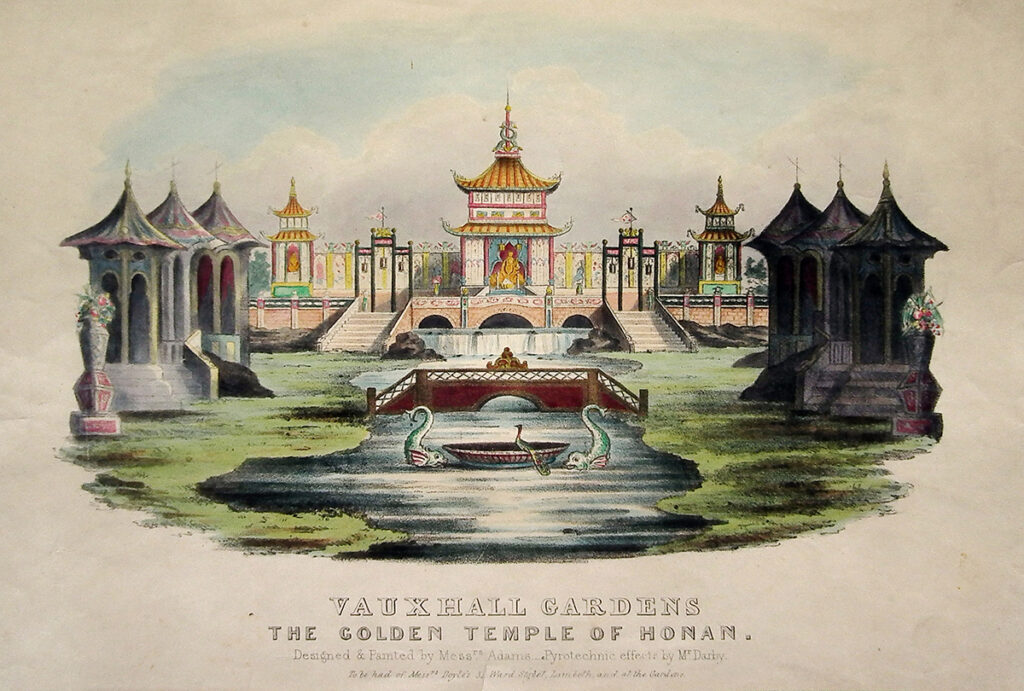

The first of the great picture-models in Wardell’s time was a huge reconstruction of the Golden Temple of Honan, or ‘Hall of the Celestial Kings’, created on the Waterloo Ground by a family of scene painters called Joseph, Frederick and Alfred Adams. [Fig.4] The Adams brothers designed and built the diorama for the 1845 season; it was intended as a stage for the fireworks of Henry Darby, and for the daring feats of a young comedian, musician and acrobat called Joel Bolton Armett (sometimes known as Joel Benedict, born in Wolverhampton in 1818), who, for added effect, called himself ‘Joel il Diavolo’. Joel used the Picture-Model of the Temple of Honan as a backdrop for his spectacular descent suspended on a pulley under a diagonal tight-rope, with live fireworks attached to various parts of his costume, no doubt announced by a crescendo in the music. [Fig.5]

These picture-models had to be built to a very high standard of construction, capable of withstanding not only the British wind and weather, but also the tension of tightropes attached to the highest points, with the added weight of a human being suspended from them. However, even though the Temple of Honan may have been inspired by the 1843 book China illustrated by engravings from Thomas Allom’s drawings, the Adams brothers clearly saw no real need to be topographically accurate – a suitably ‘oriental’ scene was enough to suggest what they needed. So Vauxhall’s ‘Golden Temple of Honan’ actually bore little resemblance to the original in Guangzhou, but it hardly mattered – very few people would have known any different. It had a ‘Chinese’ bridge over an artificial lake with fountains at the front, and three pagoda-like structures with golden idols inside; when Darby’s fireworks were set off around it, celebrating ‘the Buddha Feast of the New Year, on the First Day of the First Moon’, it must have looked like something out of a Hollywood epic. [Fig.6] A writer in The Pictorial Times of May 1845, after lamenting that the Gardens had been about to be developed for housing, goes on ‘But lo! it has become resuscitated – the garden again blossoms and blooms – operas, ballets, splendid fireworks, all that can allure the eye or charm the sense, is to be exhibited; and who would stay away?’ He then goes on to eulogise the ‘Buddha Temple of Honan’ explaining that the three Buddhist idols represent the past, the present and the future.

The following year, 1846, the picture-model was extended and developed to make it even grander and more impressive; a tall pagoda was added on the left, from which ‘Joel il Diavolo’ made his terrific descent mounted on a flaming and fire-breathing dragon. [Fig.7]

Following its two-season outing at Vauxhall (1845 and 1846), the Temple of Honan was bought by W. & J. Beardsley of the Pomona Gardens, Hulme, Manchester. It was later dismantled and transferred in a reduced form to the small Ranelagh Gardens in Margate, Kent, where it was recycled by the proprietor J. Kevis as ‘an Entertainment hitherto unequalled in Kent’ and ‘lately exhibited at Vauxhall Gardens in London’.[3]The handbill currently with Grosvenor Prints, Covent Garden, Stock ref: 57170. That same year, in 1847, Joel il Diavolo had a new backdrop for his daredevil routine. His winged figure now thrilled Wardell’s audiences by flying like a shooting star, head-first across the night sky from the Campanile of St Mark’s on the Piazzetta in Venice, ‘surrounded by blazing fireworks, and with squibs and crackers in his cap and heels’.[4]Edmund Yates: His Recollections and Experiences. London: Richard Bentley (1884), p.140.

This time topographical accuracy was more important, so the Adams brothers built their model of ‘the Grand Square of St Mark… with every regard to Architectural correctness and Beauty.’ [Fig.8] The audience’s view was again across water, to magnify the effect of the fireworks. The Illustrated London News of 17 May 1845 was clearly relieved to find that there was now no trace of the ‘dreary efforts to appear festive’ that had so badly infected previous seasons, ‘and the present proprietor seems determined to do everything on a sensible and satisfactory scale’.

Joel il Diavolo, who had appeared in the same guise before his Vauxhall exploits, flying from the dome of Cheltenham’s Pump Room as Mercury in 1840,[5]Cheltenham Free Press, 15 August 1840. made no further appearances at Vauxhall. In 1848, it is likely that he had travelled to Ireland to work – in that year he married Barbara Donovan, an actress, in Cork. Soon afterwards, he moved back home, and became Acting Manager to Charles J. Dillon at Wolverhampton’s Theatre Royal. But ‘il Diavolo’ was to return – In the 1850s, Joel took his skills elsewhere, appearing in his alter ego both at Cremorne Gardens in London, and, in 1855, at its namesake in Melbourne, Australia. Australia’s pleasure gardens, of course, were open in the Southern Hemisphere’s summer, when England’s gardens were closed for the winter.

It can safely be assumed that Joel’s highly risky performances with fireworks caused him many burns and other injuries, so he would have been under pressure from his family to find an alternative source of income. But performing was clearly in his blood, and he was soon calling himself a ‘pantomimist’. In the winter of 1857/8, he took on the role of the Clown in the pantomime of Little Bo-Peep.[6]There is a brief obituary for Joel at James C. Dibdin, The Annals of the Edinburgh Stage. Edinburgh: R. Cameron, 1885, p.464.

By 1861, Joel had moved back, with his wife Barbara and their four children, to Lambeth, where employment prospects were more promising, and his stated career as ‘pantomimist in the theatre’ continued. The role of a pantomime clown was hardly less dangerous or strenuous than his high-wire act, so by his early fifties he appears to have given up performing, altogether and he was calling himself the Manager of a Soap Works on his daughter’s marriage entry in Lambeth in 1870, and a ‘house agent’ in the 1881 census. After living most of his life in the face of danger, Joel managed to die peacefully at home, just around the corner from Vauxhall Gardens, on 3 April 1887, aged nearly 70.

For the few years following 1845, William Battie, ‘Principal Artist to Vauxhall’, was given command of the picture-models. Battie put together a team to design the constructions, which included at least one of the Adams brothers, a painter called J.G. Day, and a M. Fenouillet, ‘Artist to HRH Prince Albert’, who had already produced some exotic interiors for Vauxhall. These team-leaders had numerous assistants on hand, and the construction team was led by Vauxhall’s ‘mechanist’, Mr. B. Phillips.

The first production of Battie’s team was the ‘Grand Pictorial Model of Constantinople’ in 1848. An illustration of this appears on a handbill of 1848 at the Lambeth archives, and although it includes many recognisable features of Byzantine and Islamic architecture, it appears not to be a topographically accurate rendition of any known view, but a composite cityscape made up from several sources; one of these must have been Julia Pardoe’s two-volume Beauties of the Bosphorus published by George Virtue in 1838, with illustrations after W.H. Bartlett. This picture-model too was used for firework displays, although not for the kind of dramatic pyrotechnics that had accompanied the Hamburg scene. The fireworks seen over the model in the pictorial poster in the Evanion collection at the British Library are very tame in comparison. Darby was still the pyrotechnician, but the drama of this view derived from the subject, so did not need fireworks to impress the audience.

By the end of the 1840s, Vauxhall’s huge picture-models were taking on a new importance in the marketing of the Gardens; although Vauxhall had a railway station from 1845, the final section of the Southampton line from Vauxhall to Waterloo was opened on 11 July 1848. Vauxhall Station was adjacent to the Gardens; indeed, it is said that dead fireworks would land in the open third-class carriages, and that travellers could clearly see the Gardens from their seats. The sight of Vauxhall’s picture-models, even in daylight, must have distracted from the tired look of the place, and attracted new paying customers. There is no doubt that, despite poor weather, the 1848 season was a good one for admissions, but this was less to do with the picture-model than with the other main attractions – principally the jazz-dancer Master Juba, and the lion tamer Isaac van Amburgh.

In the first full year of the Waterloo railway line’s operation, passengers were treated to an unusually atmospheric picture-model; the Waterloo Ground was filled with a vast scene of Lake Como in Italy, which presumably made full play of the reflective water. Although no illustration of the Lake Como picture-model survives, it is safe to assume that it was a view of the lake, probably with a village like Bellagio in the foreground, and the foothills of the Alps rising out of the lake, the Bernina mountains in the distance. This was a favourite view of Victorian artists, and remains so today.

The following year, Battie moved the scene to Moscow, and built a scale-model of the Kremlin. Like Adams’s view of Venice, architectural correctness appears to have been observed, even if the buildings were rather crowded in. However, part of Lake Como appears to have migrated to the Russian capital, and the Italian alps appear in the background. Famously, there are no mountains around Moscow, which is itself on the highest ground in the region, but Battie’s picture-model definitely showed the city against an alpine backdrop, presumably to mask the views of suburban London beyond.

The illustration of the scene in The Illustrated London News [Fig.9] gives less prominence to the picture-model, and more to the Nassau Balloon over-flying the cityscape, and the cheering crowd of visitors, amongst whom, on the left, can be seen the ‘Nepalese Princes’ in the audience. This Nepalese group actually comprised the Nepalese Prime Minister, Jung Bahadur with a high-ranking military entourage; they visited Vauxhall twelve times between 22 June, when their arrival was greeted with a gun salute, and 5 July. They were naturally fascinated by Charles Green’s great balloon, especially for its military potential, but they may also have been interested to see the Kremlin, as Moscow was not on their itinerary for this journey.

The regular featuring of Vauxhall Gardens in The Illustrated London News may have been prompted by that original criticism, quoted above, and the fact that it must have been taken to heart by Vauxhall’s proprietors; they did indeed ‘invest significantly’ and become ‘more creative and innovative’. The resulting picture-models received their due recognition in The Illustrated London News’s pages over several seasons.

The Kremlin scene was replaced the following year by one of the most mysterious of all the picture-models at Vauxhall, and probably the largest. This was William Battie’s ‘Stupendous Picture of the Temple of Concord’ [Fig.10] launched on the grand fete for the birthday of Queen Victoria on 31 May 1851. The proprietors claimed that this was ‘the Largest Painting ever undertaken’. The measurements have already been given in the opening paragraph.[7]Lambeth Archives, Minet volumes III, f.243.

The mystery here is the title – the image of the painting on the 1851 handbill appears to show a neo-classical piazza with a central fountain, around which are ranged five near-identical façades. These façades relate closely to the church of San Giovanni in Laterano in Rome, completed in 1735, which in turn shows the influence of the church of SS Luca e Martina close to the Roman forum, re-built c.1635. But how does this relate to the Temple of Concord?

In the 1770s, Francesco Piranesi, son of the more famous Giovanni Battista Piranesi, produced a set of etchings of Rome, one of which included the church of SS Luca e Martina, with Roman ruins in the foreground. This was titled ‘Altra Veduta degli avanzi del Pronao del Tempio della Concordia’, or ‘Another View of the ruins of the Portico of the Temple of Concord.’ Battie may have seen Piranesi’s print, or something like it, and wanted to create a notional reconstruction of the Roman temple. He clearly had little idea of the actual content of the print, or that the church was only 200 years old and never part of an ancient Roman temple. The dome on the central building in Battie’s scene is very close in design to the dome on SS Luca e Martina.

So why go to the trouble of designing and building at Vauxhall Gardens such a dubious reconstruction, when his other picture-models all relied on good evidence? The answer to that may lie in the history of the original classical temple itself, built in the 4th century BCE. Its purpose was to symbolise the aspiration towards a new reconciliation between patricians and plebeians, and harmony between the social classes. As the mixing of the social classes was one of the outstandingly positive features of Vauxhall, maybe this was what was in Battie’s mind, or in the mind of Robert Wardell, who was by 1850 the director and sole lessee of the Gardens. If this is the case, it really did not matter whether the topography was accurate or not, it was the symbolism that mattered, even if few of Wardell’s visitors appreciated the full meaning.

One of the features of Battie’s vast picture-model of the Temple of Concord was that it was embellished with many transparencies. Vauxhall’s transparencies, huge paintings in tinted varnish on linen with lamps behind, were normally allegorical and symbolic, so transparencies in and around the Temple of Concord could have celebrated the social mix that Vauxhall’s typical audience represented. Sadly, there appears to be no surviving report of the 1851 display to give us a better idea of it. The rather feeble fireworks shown on the handbill could not have been the main attraction of the evening. The reverse of the handbill lists the attractions that backed up the picture-model, including the usual horsemanship, music and balloon flights, but it appeared in English and in French – recognising the many foreign tourists in London for the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace. Vauxhall, of course, could not hope to compete with the Crystal Palace, but it could at least cash in on the huge influx of visitors to London.

Despite being the largest painting ever undertaken, the Temple of Concord was not the last of the picture-models. That dubious honour belongs to the 1853 ‘Golden Temple of Guadma and Great Pagoda of Dagon, Rangoon’. This return to the exotic east was the last great work of the Adams brothers at Vauxhall and was based on drawings furnished by the museum of the East India Company. [Fig.11] Burma (today Myanmar) was an enemy of Great Britain in the early years of the 19th century, having attempted to expand into British India. During the second Anglo-Burmese War, Rangoon (Yangon) was stormed by the British and captured on 14 April 1852; the Vauxhall picture-model recognised this campaign, and the fireworks of Darby’s successor William Coton, with ‘new effects’ made the most of the potential for drama. The press reported that some of Coton’s display was launched from a tower 150 feet tall, probably the top of the great pagoda or stupa.

The art of Vauxhall Gardens had celebrated British military victories around the world since the earliest days. Peter Monamy’s paintings of the 1740s, and Francis Hayman’s huge Seven-Years War paintings in the Pillared Saloon were notable examples, but reconstructions of the Battle of Waterloo had become a regular feature, both at Vauxhall and elsewhere. The Anglo-Burmese wars, which combined dramatic action with exotic scenery and topical interest would have been an irresistible subject for Wardell and his artists, and for his audience as well.

This audience appears in force in an engraving of the following year (1854) showing Charles Paternoster’s great balloon, The Royal Sultan, ascending from Vauxhall with the picture-model of The Great Pagoda of Dagon in the background. The sheer scale of the Adams brothers’ structure is made very apparent in this dramatic print, which shows it as little short of life-sized. [Fig.12] How long after its first two years the Pagoda stood at Vauxhall is not known. It was certainly the last of Vauxhall’s great picture-models, and the money invested in it would have justified a longer life than some of the other scenes; it is possible that it survived through Wardell’s management, which ended after the 1856 season, and does not appear to have travelled to any other venue.

The Gardens failed to open at all in 1857. After that, Vauxhall Gardens was clearly doomed to close, as no worthy successor could be found for Wardell, so no new significant investments were made. The final but inevitable closure happened on ‘Positively the last Night Forever’, 25 July 1859, with the demolition teams moving in soon after. However, in the two decades before this, Vauxhall had developed and perfected its last great contribution to the art of visual entertainment – the magnificent picture-model, which, in turn, was the direct ancestor of Hollywood’s epic film sets less than a century later, transmitted as they were through the pleasure gardens set up in many American cities, occasionally with staff or managers who had migrated from England. Vauxhall Gardens may have closed in 1859, but its legacy continued in many forms for a long time afterwards.

References

| ↑1 | Illustrated London News, 13 June 1846. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Standard, 28 August 1841. |

| ↑3 | The handbill currently with Grosvenor Prints, Covent Garden, Stock ref: 57170. |

| ↑4 | Edmund Yates: His Recollections and Experiences. London: Richard Bentley (1884), p.140. |

| ↑5 | Cheltenham Free Press, 15 August 1840. |

| ↑6 | There is a brief obituary for Joel at James C. Dibdin, The Annals of the Edinburgh Stage. Edinburgh: R. Cameron, 1885, p.464. |

| ↑7 | Lambeth Archives, Minet volumes III, f.243. |