This article appeared in the Vauxhall Society’s Newsletter January 1982

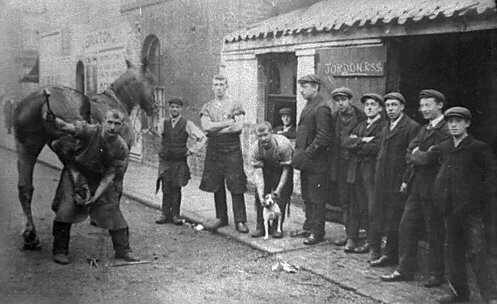

Forge in Palfey Place

Much has been said and written in recent years about the decline of industry in the inner areas of London, and with it the decline of opportunities for local employment. Whatever the causes of this change, it is interesting to look back a hundred years or so, and see what these industries were that allegedly are so missed. Certainly they provided employment, but many on only a relatively small scale and in conditions which were very far from safe, hygienic or secure.

Looking at maps and directories covering our area in the 1870s and 1880s, we notice the remarkable number of industries that have disappeared almost without trace, particularly in the neighbourhood of Lambeth. Perhaps the largest and most prosperous of these was pottery, with the Thames waterfront once crowded with rival firms (not only Doulton‘s), making every conceivable artefact from porcelain, stoneware and earthenware. Nearby were also the Vauxhall glassworks and the sanitary engineering works in Lambeth Palace Road (then called simply ‘Palace Road’).

Engineering works and foundries are the next most numerous industries to have all but disappeared. The largest occupied a site in Baylis Road (formerly called Oakley and Gibson Streets) which was later covered by the Peabody Buildings. Two engineering works were also situated in York Road, where the Shell Centre now is and behind them, nearer the river, were an iron foundry and moulding works. Iron and brass foundries tainted the predominantly residential neighbourhood of Pearman Street, and behind the Old Vic, off Waterloo Road.

The number of timber yards, sawmills and builder’s yards in old Lambeth undoubtedly reflects the irresistible expansion of London during the 19th century. The riverside was the traditional location for these types of industries, since their raw materials could for a long time only be moved in bulk by water. The South Bank was in the 18th century the site of Eleanor Coade’s factory for producing the famous patent artificial stone – Coadestone. A hundred years later, in the 1870s, the site of the present County Hall was occupied by builders’ yards, a timber yard and also a flour mill: the present Jubilee Gardens by three more builders’ yards, four sawmills, a limekiln and numerous wharves and cranes.

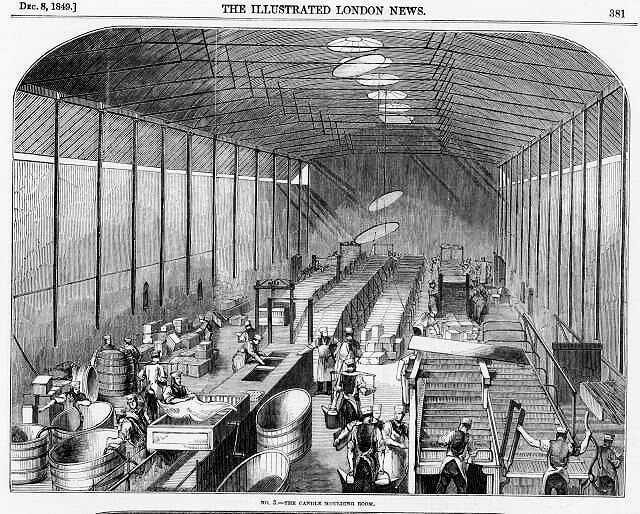

Price’s Candle Factory

Among the smelly and even noxious industries of the area were the Lion Brewery on the site of the Royal Festival Hall, and lead works on the site of the Queen Elizabeth Hall and Purcell Room. A candle and night-light works lined Carlisle lane (formerly Carlisle Street) approximately where the car-park now lies behind the flats in Royal Street. A candle manufactory was also to be found in the space between Lambeth Road (previously Church Street) and Paradise Street, where the Metropolitan Police garage now stands. A distillery was alongside, while behind Kennington Road police station was the Wellington emery and black lead works, giving its name to the present housing development known as Wellington Mills. Another kind of distillery, the vinegar works founded by Beaufoy at Vauxhall is still very much in operation.

There were some more highly skilled craft enterprises here and there: a railway signal works in Lancaster Street (off London Road), a colour works in Baron Place (off Waterloo Road) and, in Addington Street, a fire-engine factory. Off Walnut Tree Walk stood a coach-builders, which became involved with the manufacture of horse-buses at an early date. The premises were eventually converted to a commercial vehicle garage, last used by Trust Houses Forte, and demolished sin the early 1980s. The entrance is still recognisable at the time of writing by the high rectangular archway which was cut in the frontage of a row of ordinary terrace houses.

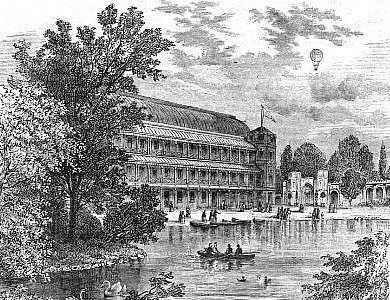

The Lion Brewery

Stables were a prominent feature of the 19th century townscape, and are a recurrent item on the maps of a hundred years ago. A large concentration existed off Cornwall Road, in the vicinity of Roupell Street. Their modern parallel perhaps is the bus yard further down the same road, where the Japan Works used to produce its lacquers. The numerous public houses shown on the old maps, though hardly a focus of employment, bear witness to the taste as well as the social life of people who laboured in all the industries mentioned here. Similarly with the music halls – Astley’s at the end of Westminster Bridge, the Surrey Theatre at St George’s Circus, the South London Music Hall in London Road, the Victoria Palace (Old Vic) and The Bower in Upper Marsh (now obliterated by the widening of the railway approaches to Waterloo).

Music Hall at Surrey Gardens

One conclusion from this brief survey would be that although the centres of skilled and manual employment have greatly reduced in number, the total of jobs available has greatly expanded as a result of office development. But offices – and roads – have also replaced housing, and that has probably changed the character of our area much more than the contraction of local industry.